CAMP Study Day at MoMA

Duration: 03:17:20; Aspect Ratio: 1.778:1; Hue: 115.591; Saturation: 0.022; Lightness: 0.227; Volume: 0.082; Cuts per Minute: 1.110; Words per Minute: 131.344

Summary: CAMP Study Day, brings together leading scholars of media, law, cinema, and visual art on the occasion CAMP's exhibition Video After Video: The Critical Media of CAMP.

Speaker Abstracts:

- Lawrence Liang

Using the three works in Video After Video: The Critical Media of CAMP as milestones, I will

trace a narrative arc through CAMP’s practice over the past two decades, focusing on the

evolution of their ethos. Drawing on key conceptual categories central to their

practices—privilege escalation, deepening access, and parasitism—I will examine how CAMP’s

artistic and political interventions expand our understanding of the ‘poetics and politics' of

infrastructure and the re-distribution of the sensible.

- Erika Balsom

Parasite, Pirate, Plumber

“We like to work within...systems as a parasite, pirate, or plumber, all of whom produce new

fictions,” said Shaina Anand in a 2014 interview. Parasite, pirate, plumber: what do these

alliterative entities share, and what different avenues do they open for thinking about the

concerns that continue to inform CAMP's practice more than a decade later? This talk will

explore this trio of marginal figures, primarily, but not exclusively, in relation to From Gulf to

Gulf to Gulf (2013).

- Debashree Mukherjee

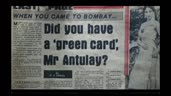

In this short presentation, I think with Bombay Tilts Down (2022) to revisit some familiar tropes

in film and media studies: the relation of cinema and the city, the politics of aerial photography,

and the techno-forensic imagination. CAMP’s latest work intervenes in these debates with

gestures towards monsoonal time, citational intimacies, and the recursive dance between

power and the people.

- Ashish Rajadhyaksha

TILTING DOWN, WITH CAMP

To understand a work like Bombay Tilts Down requires a wide canvas. This presentation uses

previous work by CAMP to sketch out a history of the city that saw the practice of cinema,

poetry and performance move alongside political movements often involving foundational

rights to speech, shelter and livelihood. Both kinds of practice came together in the way they

addressed questions of how to occupy, to reclaim the right to describe, to stake a right to the

city.

- Laura U. Marks

CAMP’s practice shows the richness and intimacy of the low-resolution image, as images are

dense with implicit information about where they come from and where they are going.

Low-res images model the light, sustainable infrastructure that will survive when more bloated

infrastructure fails.

Speaker Bios:

- Erika Balsom is a reader in film and media studies at King’s College London who specializes in

the study of artists’ moving-image practices. She is the author of four books, including TEN

SKIES (2021) and After Uniqueness: A History of Film and Video in Circulation (2017). Her

writing has appeared in publications such as e-flux journal, Grey Room, and New Left Review,

as well as many exhibition catalogues. With Hila Peleg, she was the co-curator of No Master

Territories: Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image, which began at Haus der Kulturen der

Welt (Berlin) in 2022 and will travel to Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo, next year.

- Lawrence Liang is a professor of law and the dean of the School of Legal and Socio-Political

Studies at Ambedkar University Delhi. His work lies at the intersection of law, culture, and

technology. A winner of the Infosys award for the social sciences (2017), Liang has been a

visiting scholar at Yale, Columbia, and the University of Michigan, among other universities. He

has written extensively on the politics of intellectual property, free speech, and media cultures.

He has also been a collaborator and interlocutor of CAMP since 2005, and is one of the

cofounders of pad.ma and indiancine.ma. His forthcoming book looks at the relationship

between law and justice in popular Indian cinema.

- Laura U. Marks works on media art and philosophy with an intercultural focus and an

emphasis on appropriate technologies. Her fifth book, The Fold: From Your Body to the

Cosmos (2024) proposes a practical philosophy of living in a folded cosmos. With Azadeh

Emadi, Marks cofounded the Substantial Motion Research Network of artists and scholars

interested in non-Western approaches to media. She programs experimental media art for

venues around the world. In 2020 she founded the Small File Media Festival, which celebrates

movies that stream at extremely low bitrate. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, Marks

teaches in the School for the Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver.

- Debashree Mukherjee is associate professor in the Department of Middle Eastern, South

Asian, and African Studies (MESAAS) at Columbia University, and co-director of the Center for

Comparative Media. She is the author of Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City

(2020) and editor of Bombay Talkies: An Unseen History of Indian Cinema (2024). Her current

book project, Tropical Machines, develops a media history of South Asian indentured migration

and plantation modernity from the 1830s onward, and has been awarded an ACLS fellowship

for the year 2025–26. Debashree edits the peer-reviewed journals BioScope: South Asian

Screen Studies and Screen, and has published in journals such as Film History, Film Quarterly*,

Feminist Media Histories, Representations, MUBI’s Notebook, and Modern Asian Studies.

- Ashish Rajadhyaksha is a film historian and occasional art curator. He is the author of Ritwik

Ghatak: A Return the Epic (1982), Indian Cinema in the Time of Celluloid: From Bollywood to the

Emergency (2009), and The Last Cultural Mile: An Inquiry into Technology and Governance in

India (2011). He is the editor of Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema (with Paul Willemen)

(1994/1999), In the Wake of Aadhaar: The Digital Ecosystem of Governance in India (2013), and

a book of Kumar Shahani’s writings, The Shock of Desire and Other Essays (2015). Among his

curated projects is the “Bombay/Mumbai 1992–2001” section (with Geeta Kapur) of Century

City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis at Tate Modern, London (2002); You Don’t

Belong festival of film and video, Beijing, Shanghai, Guanghzhou, and Kunming (2011);

Memories of Cinema at the IVth Guangzhou Triennial (2011); Make-Belong: Films in Kochi from

China and Hong Kong, Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2015); and the exhibition Tah-Satah: A Very

Deep Surface: Mani Kaul & Ranbir Singh Kaleka: Between Film and Video at the Jawahar Kala

Kendra, Jaipur (2017).

Good afternoon.

Welcome to those of you here on 53rd Street and also to those of you joining us online internationally. I'm Stuart Comer. I'm the Lonti Ebers Chief Curator of Media and Performance here at the Museum of Modern Art and it's my great pleasure to welcome you all to the CAMP Study Day today.

Introduction

Stuart Comer

Where to look when considering answers to the question, what is

Video After Video? Today for Midtown Manhattan we consider propositions formed on a rooftop in Mumbai, part of a studio gathering artists, technologists, activists, archivists, lawyers, and other thinkers and kindred spirits under the name CAMP.

Four letters that reflect many thousands of possible acronyms, each an open equation and an opportunity to rethink everyday life and the infrastructures built to define it. CAMP's studio has become one of the most urgent and exciting crucibles internationally for the exploration and examination of public images, what they tell us about the world and our capacity to act within it.

Here, in this exhibition, video is posed as a live technology, one that is integrated closely with human life in real time through telecommunications, transport, trade, and the internet. But also a technology made up of its quickly proliferating afterlives, an expanded field of image streams that CAMP transforms into a living archive, whose phantoms have real-world consequences.

And so here on the left you see some of the permutations of the many thousands of acronyms I mentioned. A huge shout out to MoMA's graphic design team for working closely with the artists to, yes, and the introduction of wrong font into our graphic design lexicon.

So hopefully most of you have seen the exhibition, but for those of you who have not, this is the entrance to the show.

And I just wanted to quickly show this image, which our C-MAP, former C-MAP colleague and fellow, and now the assistant director of our international program, Christina Noel, dug up from the archive a week or two ago.

This was our first C-MAP trip to India in 2015, and we met Shaina and Ashok at that time.

I had been following their work for some time when I was still at Tate in London, but it was really thrilling to finally meet them and have the opportunity to see their exhibition at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Mumbai and to really get a deep dive into the work.

It sparked a dialogue that continued and has to some extent manifested in the exhibition that you will see upstairs and today's Study Day.

The work on view comprises three individual works or installations, first

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf, an assemblage of cell phone videos collected from sailors working in Dhow boats across the Gulfs from Sharjah to Somalia, produced on the occasion of the Sharjah Biennial (Documenta 13). An incredibly important shift in the documentary form, one that is truly collectively produced, that really charts the role that cell phone cameras have taken in our lives and really charts that path from very pixelated digitized images to the more high definition cameras we have today.

We've tried to evoke the plazas in Sharjah where the work was first shown and also sort of a nautical language that evokes the boats themselves.

Khirkeeyaan

Khirkeeyaan, the earliest work in the show, which long before Zoom created a network inside of Delhi in the inner city neighborhood of Khirkee, using very rudimentary CCTV webcam technology and cable television technology to literally cut a slice through the hierarchies and structures of class, caste, gender, and beyond that had traditionally defined that neighborhood and created new dialogues between recent migrants, established housewives, factory workers, and many more, creating a really open-ended communication system that's really thrilling to watch and I hope you do dedicate some time.

And finally,

Bombay Tilts Down, really an incredibly magisterial work premiered at the Kochi Biennial a couple of years ago. We were very thrilled to be able to acquire this work for MoMA's collection recently and it is a key anchor in the exhibition that takes the expansive view of

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf and even the microscopic view that you see in

Khirkeeyaan, folds that into this incredible accordion fold panorama in which many vectors of the camera map out or really create a counter mapping of Bombay.

And it was shot during the pandemic, you'll hear much more about this work in the various presentations today, but really I think a significant contribution to the field and we're thrilled to have it on view here at the museum.

So marking the occasion of this exhibition, today's Study Day, and the exhibition is on through July 20th by the way, today's study day helps build on the exhibition's mission to help CAMP realize one of the group's stated goals: to develop new or reconfigured distribution platforms, cinemas, libraries, exhibitions, books, websites, performances, with both new concepts and materials, sensibility and sensuality, to take opportunities to change, to be hospitable to ideas and to people.

And on the note of hospitality, I would like to join MoMA and my co-curator Rattan in warmly welcoming Kiran Nadar Museum, Mrs. Kiran Nadar, Roobina Kurode, the director, Deepanjana Klein, Radha Mahendru, Pallaavi Surana, and Premjish Achari.

We are so delighted to have you here. This is a really exciting collaboration between MoMA and KNMA.

I'm particularly pleased to welcome them to New York, all the way from Delhi, to really support the vital intellectual exchange that we've had in the preparation of this event and the incredible support they've offered to make it happen.

For those of you unfamiliar with KNMA, it's the first private museum of art exhibiting modern and contemporary works from India and the subcontinent, open to the public in January of 2010. Located in the heart of New Delhi, it is a non-commercial, not-for-profit organization that exemplifies the dynamic relationship between art and culture through its exhibitions, publications, educational and public programs.

The ever-growing collection of KNMA is largely focused on significant trajectories. Its core collection highlights a magnificent generation of 20th century Indian painters from the post-independent decades and equally engages the different art practices of the younger contemporaries.

This latter commitment, of course, has led to the important collaboration that allows us to gather here today.

KNMA, too, acquired

Bombay Tilts Down, and their commitment to CAMP's work has been very important, of course, in the conversations that we've had. And before I welcome Mrs. Kiran Nadar to the stage, I just first wanted to thank the speakers who have gathered here today alongside the artists Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran from CAMP.

We're so delighted to have you here.

Erika Balsom, Laurence Liang, Dabashree Mukherjee, and Ashish Rajadhyaksha. We're thrilled to have you from many corners of the world to join us in celebrating and thinking about CAMP's work today.

I would also like to deeply thank many colleagues at MoMA for bringing us all together as well. First of all, our director, Glenn Lowry, who's been very supportive of the region in general and certainly of this partnership with Kiran Nadar Museum.

So Sarah Suzuki and also Jay Levinson, the director of our international program, whose C-MAP initiative allowed us to travel to India in the first place. And also to bring in my co-curator, Rattan Singh Johal, as our first C-MAP fellow dedicated to South Asia, who has since gone on to many other major achievements, now based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

But crucially, more than just a collaborator, but really a crucial voice in authoring this exhibition and today's study day. So Rattan, thank you. Also...

Also Lilia Taboada, the curatorial assistant who supported this exhibition. Huge thanks to Lilia.

And Ananya Sikand, the current C-MAP fellow.

And what had been the C-MAP Asia group has now morphed into C-MAP Bombay, which is the first time that we've focused one of the groups on a city rather than a region or a territory. So it's particularly exciting to have that research underway at MoMA as the CAMP exhibition is currently on view.

This event absolutely could not have happened with our completely incredible and dedicated colleagues and learning and engagement led by Nisa Mackey. Huge thanks to Leonardo Bravo, Adelia Gregory, Cam Thompkins, Jose Camacho, and Eddie Amante.

We're thrilled to be working with you and really grateful for the huge effort you've put into bringing this event to life today. Thank you.

And finally, to our colleague Keva, who has been instrumental in engineering the performance that hopefully many of you will see tonight in the gallery, and our incredible AV team, Aaron, Travis, Paul, Mark, and Charlie.

We couldn't do it without you. Huge thanks.

And without further ado, I would like to warmly welcome Mrs. Kiran Nadar to make some introductory remarks. Thank you all for being here.

Thank you, Stuart.

I'd like to welcome everybody here for this really important day where we're going to see the study group, study of the work of CAMP, which we have put together as partners of MoMA.

It's a great honour for KNMA to have this association with MoMA.

Glenn has been a real mentor for us, and so have other people at MoMA. We have had a lot of support from them for KNMA, and it's been a learning process for us.

So I'd like to thank MoMA for all their assistance to us.

I'd also like to say that this particular work was acquired.

We acquired the first edition.

So I just thought I should mention it. We acquired it at Kochi, and it is one of the most phenomenal works that you'll get to see, for those of you who haven't seen it. And it will also hopefully be shown at our launch of the new KNMA space in 2027.

So here's keeping fingers crossed that we are able to do it, as well as it's being done at MoMA today. And that it will be a memorable time for us as well.

I'm not going to take out too much more time. Oh, just to say that our museum will be opening in 2027 in India, and I hope a lot of you will visit us then.

Now I'm going to ask Rubina, the director of KNMA, and our chief curator, to come and say a few words. Rubina.

Thank you, Kiran.

Hello, everyone.

It feels great to be here once again in New York and at MoMA.

Amidst all of you, some familiar faces and friends I made when I was here some years ago, invited by Jay Levinson to be part of the International Curatorial Program at MoMA. That's when I met Stuart Comer, Sara Suzuki, Rattan Mol Singh, and other team members at MoMA.

And I'm proud that this association is growing stronger as we move forward.

It is indeed a momentous occasion to witness CAMP's incisive and critical practice at MoMA through the ongoing exhibition,

Video after Video, Critical Media of CAMP.

This is the first major museum show in the United States of CAMP, and I congratulate Shaina and Ashok for the extraordinary journey of CAMP, and the organizers of the show, Stuart Comer, Rattan Mol Singh, and Lilia Rocyo for the exhibition.

And I have just got some glimpses today, and I have to tell you, and I have to congratulate you for this, for the amazing display of the exhibition. It was really beautifully installed, and I also came to know that Stuart, of course, has been following CAMP's practice for very long years.

I mean, almost 14, 15 years, and I think such a practice as complex and as interesting as Shaina's and Ashok's requires that kind of engagement with it.

Curatorially, the exhibition traces the nucleus of CAMP's practiced through decades, the everyday lives of video, its global journeys, and the pervasive extent of its unending networks.

This show also underscores MoMA's significant commitment to global media, to global media histories, and showcasing transformative artistic practices from around the world.

The Kiran Nader Museum of Art is immensely delighted to be associated with the exhibition and partnering with MoMA on this CAMP study day. This collaboration, and I believe strongly has brought together diverse perspectives and insights to think together of CAMP's transdisciplinary practice.

I look forward to the speakers this evening.

It also reflects our deep commitment at KNMA to nurture critical artistic dialogues.

Just to share briefly about KNMA, we are a pioneering museum in India dedicated primarily to collecting and exhibiting modern and contemporary artistic practices of India and South Asia.

Located in the heart of Delhi, the capital city, and under the dynamic vision of Kiran Nader, our founder and chairperson, It is our mission to have and welcome, create a museum that welcomes all, it is for all, and through our collection, exhibitions, programs, and collaborations, connect arts, artists, and audiences.

While doing so in India, we have also marked our presence, through our exhibition and programs at the Venice Biennale, at the Met Breuer, Raina Sofia, Santa Pompidou, Musee Nguime, Tate Modern, at the Barbican in London, and at ACA in Australia, and now at MoMA.

Our focus has been to build one of the most seminal collections on India and South Asia, support artistic ideas and practices, and through meaningful collaborations, bring visibility and relevance to the rich and varied art and cultural expressions from our part of the world.

Our rigorous programs of exhibition making, through research, experience, our educational and cultural programs, are all geared towards the enrichment and dissemination of the arts.

I have some of our team members sitting here, from the leadership and the curatorial team, Dipanjana Klein, Radhika Chopra, Radha Mendru, Prem J. Sachari, all of them are here, some of them are here, I would say.

Currently, we are filled with anticipation at the launching of our independent museum building, which is in fact, it has expanded into an art and cultural center, covering an area of one million square feet.

Sounds interesting, engaging, and also overwhelming.

I would have, it would have multiple galleries dedicated to the collection and to temporary exhibitions, auditoriums, performing arts center, education block, cafes and restaurants, and so on.

This colossal project is designed by Sir David Ajay and Ajay Associates, along with S. Ghosh Associates, the Indian partner, and is under construction and just spoke about it. It's already creating a huge buzz and enthusiasm in our, in India and the subcontinent.

I'm especially excited to announce that this new home for art will, in its inaugural year, feature a made, amongst multiple showings, CAMP.

And it may be a significant commission or they may turn, as they may turn their distinctive sharp lens to the city of Delhi itself, offering profound insights into another complex urban landscape.

I wish to acknowledge how critically important it is to us, this relationship, our relationship with MoMA, our sharing, learning, and mentoring, and being inspired constantly by Glenn Lowry, Director MoMA, and the team, as we grow and evolve into an institution with meaning and purpose, and one that believes that art holds the promise for a better world, and a world without boundaries.

I'm pleased to call Rattanmol Singh, one of the organizers of CAMP Exhibition, a friend I've known for long.

He's the guest curator and former assistant director of the international program. Rattan.

Thank you very much.

Thank you so much, Robina. It's a pleasure to be back here and welcome you all.

And in the interest of time, I will quickly move to this slide to just give everyone an opportunity to scan the QR code and bring up the program for this afternoon and evening on your phones.

From 2.30 to 4.30, the slot we're in now, we will hear from four exceptional scholars, and that will be followed by a discussion with Stuart and myself.

We will have a quick break for informal exchanges outside the theater, and at 5.30, we'll reconvene for a keynote lecture by Laura Marks, following which at 7pm, CAMP will perform in the

Bombay Tilts Down installation for those who read the copy on the website carefully and got their tickets in time because we are now sold out.

And so with that quick overview, I will introduce our first speaker for this afternoon, Lawrence Liang. Lawrence's work lies at the intersection of law, culture, and technology. He has written extensively on the politics of intellectual property, free speech, and media cultures.

A recipient of the prestigious Infosys Award for the Social Sciences, Lawrence is currently Professor of Law and Dean of the School of Legal and Sociopolitical Studies at Ambedkar University in Delhi.

Most importantly, of course, in today's context, Lawrence has been a collaborator and interlocutor of CAMP since its inception, and is one of the co-founders of pad.ma, and indiancine.ma, the extensive digital video archives of footage and finished films.

In today's presentation, Lawrence will use the three works in the MoMA exhibition upstairs to trace a narrative arc through CAMP's practice over the last two decades, examining how their artistic and political interventions expand our understanding of the poetics and politics of infrastructure and the redistribution.

Without any further ado, please join me in welcoming Lawrence Liang.

Lawrence Liang's full presentation at CAMP Study Day at MoMA is

here

Thank you. I want to begin by thanking CAMP of course, Stuart, Rattan, KNMA, and MoMA. Thank you for having me here, and I have Ananya positioned in a very kind of, you know, strategic position with the timer there, so without wasting any time, I'm going to go ahead.

It's very difficult to speak about CAMP's rich and layered body of work in the short time that I have, but I want to begin with an acknowledgment of the curatorial logic, you know, that underlies the show, because in many ways the three works that are on display here serve as critical milestones through which we can trace a narrative arc over the last two decades of CAMP's work.

And I want to focus really on what I think is, what we can describe as CAMP's philosophy and method. And as the first speaker, I thought it would be useful for me to set a little context for viewers who may have seen the show, but not necessarily know CAMP's oeuvre.

From the perspective of a collaborator and interlocutor, the three works on offer offer us a vantage point to trace a through line that runs through their body of work and practice, because all three are visual experiments, even as they are spatial and political interventions that offer us an alternative - a cartography of control, movement, freedom and subversion.

They also mark three moments of "Video After Video". From low end CCTV, handheld digital cameras and mobile phones, and finally high res portable surveillance cameras. This is a story of CAMP, even as it is a story of technology.

CAMP's work operates simultaneously on a dual timeline. The rapidly shifting landscape of surveillance and media technology, nationally and globally on the one hand, and the evolving aesthetics and methods of their own practice.

And each of the three featured works manifest this kind of dual awareness, from hacked cable networks to high definition and CCTV. CAMP's artistic trajectory shadows the infrastructure of seeing itself, reframing it from the perspective of the artist-hacker.

One way for me to begin this is by returning in a way to the initial moment, both of friendship and collaboration with Shaina and Ashok, an origin that also coincides with the emergence of CAMP. So two early projects that I just want to turn your attention to.

The first one is a project from 2005 that was done by Ashok, called Glow Positioning System, or GPS.

GPS mounted a hand crank on a pavement in Bombay to tap into the city's electrical systems. It allowed the audience to illuminate a panoramic ring of light circling an important intersection in the city, revealing the city's hidden infrastructures, its façades, electrical circuits and architectural traces.

By lighting up façades and casting moving shadows, the crank operated almost like a magic wand, revealing a kind of wonderment latent in the everyday urban form, making visible what is usually overlooked.

Situated between the weight of colonial Indo-Gothic architecture and the constraints of archaic electricity laws, it produced an experience of cinematic lightness, of illumination and obscurity.

Simultaneously functioning as public art and infrastructural revelation, GPS established the foundation, in many ways, of CAMP' subsequent work. As a proto CAMP intervention, GPS anticipated many of the collective's later concerns, from infrastructural hacking to aesthetic interventions that laid the groundwork for what we see in

Bombay Tilts Down, where questions of access, spectatorship and urban perception become even more layered and expansive.

Even as GPS was taking place, there were two simultaneous works by Shaina.

Rustle TV in 2004 created a local TV channel within a bustling bazaar in Bangalore, and WICTV in 2005, which is when we started our collaboration, parasited a local minor language cable television channel to insert a parallel stream of commentary and coverage during an event called the World Information City Conference.

Transforming a traditionally one-way broadcast medium into a two-way channel, these interventions challenged dominant media structures and created a space for localized real-time responses within a global event.

The terrace of a local NGO became a makeshift studio from which CAMP produced its television shows, and it involved collaborating with a local cable operator to transmit content directly to the community.

Marked by the immediacy of interaction between producers and viewers enabled by video, these interventions disrupted conventional media hierarchies and demonstrated the possibilities of a more participatory media environment.

And from this foundation, you see CAMP's politics of access converging around a set of core animating principles that have shaped in many ways their artistic engagement.

The first kind of propositional form of their practice is the idea of how do you use your privilege as an artist to access spaces and infrastructures that would otherwise be unavailable, what they describe as "privilege escalation".

The second is how do you leverage that privileged access to parasite closed networks and infrastructure - surveillance feeds, port data, satellite channels - and turn the tools of control into platforms of counter-visibility, shared knowledge, or public engagement.

And finally, how do you use artistic interventions to create work and infrastructures that then redistribute and deepen access to those media infrastructures? My focus is really going to be on these two elements, infrastructure and parasitism.

Because what emerges in CAMP's practice is what I would term as a dramaturgy of urban infrastructure that intersects with media systems. Rooftops transform into studios, mobile phones document affective, and social histories of shipping. Cable networks serve as conduits of counter-visuality, and surveillance systems metamorphise into cinematic devices.

The infrastructural becomes dramaturgical, staging new relationships between space, technology, and public life.

And in most of CAMP's work, the spectator is not positioned in a classical sense. There is no fixed spectatorial addressee as in cinema, nor is there a privileged contemplative viewer, typical of the white cube gallery space.

And CAMP's spectator stands very often as a participant inside the very infrastructure that it's being tinkered with. The CCTV, the mobile camera, the cable, the window, are not external to the spectator's worlds, but embedded in them.

And the image that emerges, emerges through participation, disruption, and infrastructural appropriation. So the classical grammar of cinema gives way to an expanded cinematic vocabulary of immediacy, where the distance between the image and the spectator is collapsed.

In

Khirkeeyaan, for instance, this takes the form of a live feed. In

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf, through a performative self-representation. And in

Bombay Tilts Down, through the unfolding choreography of the camera's descent along the vertical surfaces of the city.

By hacking into the infrastructures of image making, and inventing new possibilities for visual expression, CAMP repositions video as the realm of an emancipated, entangled spectatorship, while simultaneously redefining the power dynamics of social relations across the city, the high seas, and built-up environments.

While we often speak of CAMP as a singular coherent entity, their practice is actually composed of diverse impulses, sensibilities, and energies. And two prominent instincts stand out for me.

The cinematic on the one hand, and the infrastructural on the other.

The cinematic leans towards an aesthetics and politics of the image, while the infrastructural emphasizes tactical hands-on intervention, approaching hacking as a cultural and artistic mode of engagement.

What does it mean for individual artist practitioners to hack into systems? Into codes, cables, networks, and cameras? Is there a tension between engaging with the very infrastructure of power and surveillance that CAMP seeks to critique? And how does one produce an artistic practice from within the infrastructural belly of the information beast? This might seem like a tension destined to collapse into contradiction, but I would argue that for CAMP, this very tension becomes a productive force, a generative fiction that defines their work.

Their dual stance, operating within systems to expose or reconfigure them, creates a friction between complicity and resistance, control and subversion, aesthetics and improvisation.

CAMP's practice navigates and transforms these tensions into a generative method rather than a contradiction. And it is within this tension that their radical edge emerges. Their critical engagement with media foregrounds, media not merely as tools, but as environments to be hacked, inhabited and redistributed.

This is also perhaps what is significant about the title of the show, because this is indeed

Video After Video.

The cinematic in this register is deeply intertwined with infrastructure because it's invested not only in the creation of images, but also in the complex systems that enable their production, distribution and reception.

If cinema's infrastructure organizes the flow of images in a controlled and often hierarchical manner, where production, circulation and reception are distinct, CAMP collapses these bifurcations.

Their artistic practice transforms this collapse into a methodological ethos. Films are created not with traditional film cameras, but through repurposed infrastructural channels producing parasited images.

Media structures are often designed to remain invisible. Their effectiveness in many ways hinges on a seamless integration with urban infrastructure.

In a city like Delhi, for instance, there are estimated now to be over half a million CCTV cameras or 20 cameras per thousand people. This creates a politics of concealment where power functions through what remains hidden or unnoticed.

Keller Easterling's concept of Extrastatecraft highlights how infrastructure is not a neutral ground for politics, but a dynamic terrain where power is actively deployed, shaped and contested.

And an extreme version of this might be found in the totalizing account of surveillance infrastructures by thinkers like Shoshana Zuboff, who emphasized the pervasive and coercive reach of infrastructural power.

In contrast, CAMP refuses to succumb to the unidimensional narratives of infrastructure as functional and oppressive and instead asks how we might expand their expressive affordances and capacities.

In this regard, they echo an open source ethos best illustrated by the statement by Gilberto Gil, jazz musician and former minister of culture in Brazil, who when asked how a radical musician could become a minister of culture, he answered that as a free software activist, he'd been taught that everything is porous and could be hacked, even the government.

In 2008, for instance, CAMP entered the CCTV systems of a shopping mall in Manchester to open it out to the public. They also used the Freedom of Information Act, allowing people to requisition CCTV footage of themselves, which were then brought into the public domain and became the basis of a film.

Using their privileged access, CAMP turned passive surveillance into active shared visibility, disrupting the usual flow of power and control over these images. They followed this up in 2009 in a work called

The Neighbor Before the House, in which CAMP took a surveillance camera to Jerusalem, which was then set up to enable Palestinian families to zoom in and look at their former houses from which they had been displaced.

In a very moving sequence in the film, a spectator comments that a lemon tree that existed in his garden had now died since the ground had been filled with concrete.

In the tactical art of CAMP, surveillance cameras are transformed into annotation devices that allow displaced people to visually access spaces that they don't have physical access to. To make claims on land where the zoom function of the camera flips from being a technology of control into a technology of witnessing violence and injustice.

The Neighbour Before the House

The Neighbour Before the House advances a politics of hospitality, articulated as an infrastructural challenge that interrogates who is granted entry, visibility, and access.

And how parasitism may be a mode of inhabiting and challenging how the host-guest relationship is politically skewed in the context of Jerusalem.

Laura Marks, who we will hear shortly, suggests that in a world of hypermedia, there's always a danger of the image becoming flattened to information. And nothing illustrates this better than CCTV cameras that record millions and millions of hours of footage only to be activated as legal evidence or as controlled technology.

Images, however, retain an enigmatic quality that resists full decoding or subsumption to the regime of information.

While information unfolds truthfully and transparently, Laura Marks suggests that images unfold enigmatically. They open up spaces of interpretation, affect, and multiple meanings. And in many of CAMP's work, images emerge from information infrastructures like CCTV systems and surveillance networks.

And yet, through their creative interventions in works such as

The Neighbor Before the House or

Bombay Tilts Down, these images refuse to be confined to cold instrumental functions and instead unfold as complex layers of human experience beneath the surface of technological mediation.

The modernist writer Guy Davenport once famously asserted, "every force evolves a form".

If technology is the dominant force of our time, developing a form adequate to confronting the force of technological control becomes one of the urgent imperatives of artistic practice. And CAMP's subversive grammar of media embodies this by continuously experimenting with forms that expand the expressive vocabulary of politics and aesthetics, using sensory extensions and interventions to probe and challenge the infrastructures of surveillance capitalism, thus opening out new possibilities of visibility, agency and resistance.

And in this context, Jordan Schonig's argument that the study of film has to be supplanted by the study of moving images gain salience. As technological apparatus become, which are responsible for cinematic motion, become more and more diverse and mechanically illegible, the task of accounting for the area of experiences afforded by cinematic motion takes on a new kind of urgency.

Surveillance cameras, for instance, parasite cinematic functions such as the zoom, tilt, pan, operationalizing them for regimes of monitoring and control. Cinema, in turn, needs to parasite back to appropriate the technological potential of surveillance optics in order to reconfigure the aesthetic, affective and political valence.

Schonig's examples of cinematic motion include an array of movements that can be found in surveillance cameras. Contingent motion - that captures unpredictable movements such as the fluttering leaves, swirling dust and rippling water.

Durational metamorphosis - shows slow, gradual transformations such as shifting clouds or changing light.

Five.

Spatial unfurling - uses camera techniques to emphasize changing space over physical movement. CAMP's practice and politics takes up this challenge, demonstrating how the politics of the image is inseparable from infrastructural politics.

From the negotiation of control to the creation of channels of escape, in parasiting the technological operations of surveillance optics, CAMP reworks cinematic motion as a technique of counter aesthetics where infrastructural capture is both exposed and strategically rerouted.

CAMP in many ways explores the expressive affordances of this networked world, experimenting with how the aesthetics of contingent motion, durational metamorphosis, gesture and spatial unfolding in the context of surveillance can be differently deployed.

Following Jacques Ranciere's proposition of politics as a distribution of the sensible, we can understand infrastructure as an emissary of politics insofar as it is a system that structures the distribution of the sensible.

A way of organizing who can sense what, how and when. Ranciere argues that politics is tied up with reorienting people's perceptual spaces and sensory experience.

As he writes, politics is first and foremost a way of framing among sensory data, a specific sphere of experience.

In that sense, the parasite then is the mode that produces a dissonance between visibility as political configuration and disruption as transformation. It reorganizes these distributions to make visible what infrastructure tries to keep invisible.

It renders sayable what infrastructure tries to render mute.

It reframes not just the scene but the sensorium of infrastructure. CAMP's infrastructural poetics returns in a way us to Ranciere's insights but through rooftop cinemas, pirated databases, tangled wires, hacked systems and the slow tilts of their media.

I had a section where I was going to try to connect between Michel Serres' idea of the parasite and Ranciere's idea of the distribution of the sensible. But in the interest of time, what I will do instead is to go to my conclusion.

The context of doing public art interventions in India and elsewhere is shaped by two persistent obstacles, access and infrastructure.

These constraints often result in a way in a paralysis of critical thinking and imagination, limiting the possibilities of engagement and transformation.

And to appreciate in many ways the aesthetic stakes of CAMP's practice within such a context, I turn to one of my favorite readings of a myth.

This is Italo Calvino's reading of the Perseus myth in his Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Where one of the virtues that he advocates for the next millennium is Lightness. And the myth that he reads or rereads is Perseus.

Perseus has to slay the Medusa.

And the curse of the Medusa is that if you look at the Medusa directly, you'll be turned to stone.

A petrification in a way by an overbearing reality, a condition that we all live under at the moment. So what does Perseus do? Perseus slays the Medusa through the lightest of things.

Winged shoes, a shield that becomes a mirror in which you look at the image not directly, but indirectly.

And from that debris of the slain Medusa, you also have from the form the birth of Pegasus, the winged horse, another form of lightness. The heavy infrastructure of media, its vast scale opacity and entanglement with power, risks petrifying us, immobilizing perception and agency through its sheer immensity.

To confront this without being turned to stone, we require tools of lightness, an agile politics and a playful irreverence ever attuned to the hidden currents beneath our wired world. And this is what will allow us to navigate, reflect and reimagine these systems without being subsumed by them.

CAMP confronts the Medusa of media, not through didacticism, but by donning the winged shoes of technical appropriation, the mirror shields of poetic transformation.

Their tools, whether a crank, a hacked TV feed or a CCTV camera, slips through the heavy petrification of infrastructure, using the lightest of things, wire, image, signal, to engage the weightiest of structures.

The entanglement of infrastructure and media becomes the condition of possibility for artistic appropriation that generates a certain lightness, one that we might call freedom, beauty or truth.

These, I would suggest, are the gifts that CAMP's work offers to us.

And as a return gift of gratitude, I offer you an image.

And this is an image from Jia Zhangke's film, Still Life, which is set in the context of the demolition brought about by the Three Gorges Dam. And the film is a starkly realist representation of images of buildings earmarked for demolition.

One after the other, after the other, after the other. But in the middle of the film, in the middle of this kind of realist nightmare, there is a magical moment. It's a magic realist moment where one of the buildings at night transforms itself into some kind of a UFO, refusing to be demolished and just flies away through an ascending lightness.

It's been extremely inspiring, as a friend, interlocutor, and as a fan, to follow CAMP's journey across two decades.

And as we dive deeper into an era shadowed by greater uncertainty, where artificial intelligence merges into the structures of surveillance, I can only await with excitement the next iteration of CAMP's innovative parasitic practice.

Thank you.

Thank you, Lawrence, for that stirring presentation and your discussion of CAMP's infrastructural interventions and politics of access. I promise we will return to the parasitic.

Our next speaker is Erika Balsom, who specializes in the study of artist's moving image practices. A subject on which she has authored numerous essays and four books, including After Uniqueness, A History of Film and Video in Circulation.

She is a reader in film and media studies at King's College London.

And with Hella Peleg, she co-curated the landmark exhibition, "No Master Territories, Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image", which began at the HKW in Berlin and will travel to Oslo next year.

Erika's alliteratively titled presentation, Parasite Pirate Plumber will explore this trio of marginal figures in relation to CAMP's film

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf and other aspects of that.

Erika Balsom's full presentation on CAMP Study Day at MoMA can be

Streamed here

Thank you, Rattan.

It's wonderful to be here today.

When I was first starting to think about preparing these remarks, I looked back at an interview that I did with Shaina Anand in 2014 on the occasion of CAMP's participant in the Berlin Documentary Forum 3. And in this interview, I came across a statement that immediately I knew it was the way to organize my ideas for today.

Shaina said, we like to work within systems as a parasite, pirate or plumber, all of whom produce new fictions.

So, parasite, pirate, plumber. What do these entities share? What different avenues do they open? I think we often hear about the artist as ethnographer, the artist as historian, maybe the artist as director, but these are all relatively elite professions.

And Shaina's comment, I would say, evokes a different imaginary or maybe different imaginaries in the plural.

All of them are bound to a kind of marginality.

We have three vivid figures, each with its own world. The parasite, to my mind at least, I first think of a kind of non-human realm of icky microorganisms, an ecosystem of creatures who are living off of or from others possibly, but not necessarily causing harm in doing so.

The pirate pulls us in at least two directions, both associated with a kind of theft. We have highly mythologized, adventuresome bandits on the high seas.

And we have internet users who promiscuously circulate files in defiance of intellectual property law.

And then there is the plumber, a kind of unglamorous labor who is called in to fix problems and who toils amidst water and waste.

So parasite, pirate, plumber. What I would like to do today is work through these figures to see what they might tell us primarily about

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf, but also about CAMP's practice more generally.

So I will start with the figure that Shaina mentioned last, the plumber. In the interview, I asked her to elaborate on what she meant by this, because it struck me that this term wasn't quite as readily associated with artistic practice as the other two.

And she explained, He didn't engineer the building, so he is not the main player, but someone who has a key and who often comes in when there is a crisis.

So the plumber knows how the system works. He understands, or he or she or they understand the back end. The plumber is an expert in hydraulics, dealing in flows, blockages and leaks.

In order to work effectively, the plumber has to think in terms of the whole, including the least visible parts of that whole, and has to understand what happens when that system is put in motion.

And so I started to think about if this could offer us a way into thinking about what

Video After Video might mean.

I would say in the early years of theorizing video, we find claims for its liveness, for its narcissism, for how it can create a closed circuit loop, and of course for its affiliation from television.

But what happens when smaller and smaller cameras become more and more widely available? What happens when what is not at stake is a single camera, but in fact many linked together in flows of electronic communication? What happens when these networks are used both in the surveillance, administration and management of populations, and by those very same populations in acts of surveillance, sociality and self-documentation? Well, when all of this occurs, we might be in the age of "Video After Video", a time when democratizing control or dystopian control and democratizing access stand side by side.

In this moment, video might be narcissistic, but it's perhaps more likely that it will involve a kind of relation to alterity.

It might seem extremely normal to talk about video in this way here at MoMA because it was such an important part of Stuart Comer and Michelle Kuo's exhibition Signal.

And they open their catalog essay like this video is everywhere and nowhere at once. It's around us as signals and waves and data flows, but it remains ephemeral, shape-shifting, endlessly dispersed and dislocated.

So we should not think of video then as a single material or object or a single technological device.

We should not think about it only in terms of its representational capacities, but as something diffuse and something that is inherently bound to circulation.

That potentiality is there from video's earliest days, but I think the idea of Video After Video asks us to think about whether there has been more recently a kind of rupture that has to do with video becoming ubiquitous and quotidian.

It suggests that video is subject to mutation and also might lack self-identity.

And I would just as a side note say that in this regard, we see an echo of the way that the very name CAMP also is lacking in self-identity and is something that mutates as the letters are taken to stand for lots of different words.

So these transformations in video's technical character and its widespread uses mean that the possibilities for artistic intervention are transformed.

Rather than the looping back of Nancy Holt's boomerang, we might instead think about a different diagram, an intricate arrangement of pipes, pumps, reservoirs and valves that are regulating the flow, storage and disposal of moving images across space and time.

So a complex infrastructure.

The plumber thinks in terms of this system. The plumber knows that the age of video after video demands thinking about the moving image in relation to two different kinds of reproducibility.

There's the matter of how the image reproduces the profilmic real, but also the matter of how that image is then able to circulate across networks.

And this is an idea of the double reproducibility of the moving image that I think we see immediately at the beginning of

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf when we are told that it is "a film based on actual events".

So the image is somehow documenting reality.

But then a second later, there's an addition of a second line of text, "a film based on actual events - and videos of actual events".

So there we are in a different realm, a question of the replication of images via technical devices, dispersion, dislocation and multiple perspectives reign in this film shot by 13 different named cinematographers, as well as we are told in the credits, a further unspecified number of anonymous creators of music videos across many boats and many years.

So unlike

Bombay Tilts Down, and

Khirkeeyaan, From

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf is not explicitly bound to CCTV technologies.

And yet in this genesis from so many different cameras in its radically distributed visuality, it too depends on an idea of the proliferation of electronic eyes and on an employment of the moving image happening very far from the culture industry.

So part two, pirate.

The sailors who appear in

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf are navigating seas in which piracy occurs.

But that's maybe not the most productive way to think about this work in relation to piracy.

Through this double figure, the maritime circulation depicted in the film meets ways with the world of image circulation that makes possible its production.

Both are understood in their materiality and also in their challenge to authority.

This is a film of obstinate materiality of water and fire, of cars and boxes and sacks, of wood and paint and rope, of dirt and humans and animals, but also of pixels and glitches and sensors and storage memory.

More than 90% of the world's trade occurs on water.

And yet I would say when we most often think about global circulation, we think about dematerialized flows of finance, capital, of information, or of images.

From

Gulf to Gulf to Gulf pulls the viewer down into the world of obdurate matter. And importantly, through its varied image textures, it insists that images too are things in this world.

The pirate is a disruptor. One who through this disruption reveals and contests the logic of the system.

So for both the maritime robber and for the one who traffics in images or information in defiance of copyright, nothing less than the regime of private property, that foundation of the capitalist system, is under attack.

And if, as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon famously said, property is theft, then pirates are thieves stealing from thieves. And this maybe begins to account for the kind of romantic appeal and the romantic aura that surrounds them.

Piracy is ancient, but in its informatic form, it's an especially contemporary phenomenon.

So Adrian Johns has said, ours is supposed to be an age of information, even an information revolution. Yet it suddenly seems as though the enemies of intellectual property are swarming everywhere.

I would say to some extent, CAMP align themselves with these enemies in the spirit of radical access.

There is very much a belief in an image commons that animates their practice in their work building online archives like Pad.ma and Indiancine.ma, and in making their unedited footage available there.

I would say this is especially notable given the development of their practice within a period that has seen immense control over the circulation of images, both in mass culture and by artists.

Images have never been as free as they are today. They have also never been as controlled as they are today.

And in this period, the circulation of artists moving image work has been very significantly restricted, often out of concerns that the integrity of the work will suffer if it is seen in less than ideal circumstances, but sometimes also for market driven reasons.

So while most artists have taken the path of control, CAMP have really held fast to the radical possibilities of democratization that reside in the reproducibility of the moving image, which is something I think that connects their work to a long and very vital history of radical forms of practice that challenge the values of authenticity and uniqueness that prevail within the art system.

This is an attitude that is very present in

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf in that the film is predicated on the collection and recirculation of images made largely by the cinematographer sailors and then organized by the artists in dialogue with their own footage.

Ownership here becomes scrambled, authorship becomes complicated.

Declining the label of found footage, that long-standing genre of avant-garde filmmaking, Ashok Sukumaran has noted that these images are not found, but in fact sought out.

And yet the film really decisively abandons any attempt at specifying the provenance of individual shots, such that a range of perspectives are woven together in a patchwork of different locations, experiences and image resolutions.

And so in this regard we might say that the film takes the sea not only as subject matter, but also as method. There's a kind of liquid flow that transgresses boundaries that are typically enforced, such as who is the author or who is not the author of a given image.

And so in a very loose sense we might say that these are pirated images of locations in which pirates operate.

The film was begun in 2009. This is the year of the publication of Hito Steyerl's "In Defense of the Poor Image".

Online piracy plays a very important role in this essay, one that has an essay that has been rehearsed so many times that I probably don't need to do it again here.

Furthermore, Ashok has expressed his lack of agreement with the term of the poor image, seeing it as re-inscribing a problematic class hierarchy of images at the top of which would sit the high resolution spectacle of dominant cinema.

So you have to forgive me Ashok for mentioning it again right now.

But I did want to bring it up because I would say that in 2025 the value of this text perhaps has changed from the moment of its initial publication.

For me at least today the value of this text is primarily in its description of a precise historical moment, one that is no longer our own.

But one that is the moment in which

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf was first begun.

And this was the time when an intensely compressed pixelated image figured as the visual sign of a novel mode of image production, the cell phone camera.

And so what flexibility of capture and ease of copying these devices possessed as affordances, they had the limitation of image resolution.

In 1979, in a radically different context, Rosalind Krauss talked about the grid in painting as anti-natural, anti-mimetic, anti-real.

She said it's what art looks like when it turns its back on nature.

So when we see the pixel grid assert itself so strongly in these gorgeous painterly low definition images of

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf, carving the fluidity of the sea into all of these jagged blocks, we might say the same thing occurs.

An anti-real grid in which art turns its back on nature and toward the affordances and limitations of new forms of image capture.

But if we accept that idea, we also have to accept that a kind of tension arises because the low definition image in this period is also very closely associated with authenticity and contingency with a kind of claim on reality.

So the low definition images of

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf for me hover in this interesting space of uncertainty and very much speak to how digital imaging technologies in this period are associated on the one hand with new forms of capture that produce intense reality effects.

And on the other hand with a kind of attenuation of referentiality that puts pressure on photorealism and pushes toward abstraction.

Last part, the parasite sort of picking up a little bit from the last talk.

So the parasite is a relational figure.

Michel Serres writes that it brings the system's balance or the distribution of energy into fluctuation.

It irritates it, it infects it.

The parasite knows that there is no outside. It's characterized by enmeshment, dependence, or what Anna Watkins Fisher has called an intimate cohabitation with the host.

We hear a lot today, I think, about Audre Lorde's ideas that it's impossible to dismantle the master's house with the master's tools.

I think this is a really excellent idea in many contexts. It helps me think, for instance, what's wrong with a film like Barbie, a film that is like

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf - a musical, but is different from it in basically every other way.

But the parasite offers a way of thinking that is very different from Lorde's idea. It offers us a way of thinking about what it might mean to chip away from the interior of a system that can seem totalizing but maybe isn't.

The moving image in all of its forms is a profoundly non-innocent medium. It's intimately complicit with colonialism, racism, extractivism, various other forms of domination and degradation.

It's a key vehicle of algorithmic governmentality. It's a master's tool.

But the parasite knows that the way out is the way through. And so this might be, for instance, why CAMP looks so often to CCTV technologies, but it might help us to think more generally about why the moving image is their preferred format of choice.

We could also deem parasitical those forms of artistic practice that appropriate or repurpose existing materials.

Before it was used as a term in biology, the parasite was a social phenomenon. It referred to a guest invited to sit at a table next to a host of a higher social position.

So the parasite in this context doesn't cause harm, but it draws on the resources of the host by existing in relation or by staying nearby.

And by choosing the word nearby, I'm sort of purposely invoking a guiding principle of Trinh T. Min-ha's counter ethnographic practice.

We might say that

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf stays nearby or sits alongside the cinematographer sailors.

It's a work of participatory documentary. That's an ethnographic form with a long history and also a very contested one.

It's often associated with attempts to overcome the power asymmetry between filmmaker and subject. The idea there is that handing over the camera will give the subject the opportunity to represent themselves.

And we see this in

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf with the sailors filming as they like, commenting on how they want to shoot and what they want to do. But participatory documentary has also been very contested.

Pooja Rangan has noted, for instance, that it's often associated with an attempt to give voice to the voiceless that we should be skeptical of.

I would say that

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf participates in this lineage of participatory documentary while dodging the problem that Rangan identifies. It does not give voice to the sailors. It does not speak about them.

It stays alongside them. It stays nearby, re-presenting their images, crucially without much explanation or commentary. And I see that modesty really there as a sort of ethical gesture.

I've already noted that the film's interest in materiality evokes the materiality of bodies and the materiality of media.

And I think we can say that the idea of the boat and the image as twin mediums of transport is something that puts the entire artwork in a reflexive light. Notably, its first two sequences raise the question of representation itself.

We see two men mugging for the camera, lip syncing to songs and re-enacting gestures from genre films. And we see them assembling, other people assembling a model boat, a kind of mise-en-abyme of the floating workplace.

So we have here two opening sequences that are depictions of creative acts that highlight from the beginning, artifice and authorship.

The work, I think, really overcome this false binary of realism and reflexivity that has historically marked the boundary between documentary and the avant-garde. But it is a boundary, I would say, that is increasingly wonderfully blurred in practices such as CAMP's.

Thank you, Erika.

Our next presenter is Debashree Mukherjee, who is the author of "Bombay Hustle, Making Movies in a Colonial City", and the editor of "Bombay Talkies, An Unseen History of Indian Cinema".

She is Associate Professor in the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies at Columbia University, where she also co-directs the Center for Comparative Media.

Debashree is currently working on a media history of South Asian indentured migration and plantation modernity from the 1830s onward.

In today's presentation, Debashree will think with

Bombay Tilts Down from 2022 to examine how CAMP's latest work gestures towards what she terms monsoonal time, citational intimacies, and the recursive dance between power and people.

Please join me in welcoming Debashree.

Debashree Mukherjee. Okay, so very bright lights.

Thank you, mainly I mean, first of all to Stuart, and Rattan, and everyone at MoMA, for inviting me to think with CAMP, artists, friends that I've known and collaborated with in very minuscule capacities over the years, years, but a real joy to see the latest work here.

So I'll be talking a bit today about

Bombay Tilts Down.

Debashree Mukherjee

So we'll get at some point to this idea of Tilt Down Post-humanism.

berger

The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sunset. We know that the earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation never quite fits the sight.

The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sunset. We know that the earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation never quite fits the sight.

Now these words are the opening lines of John Berger's classic text, "Ways of Seeing" from 1972.

He continues, "soon after we can see, we are aware that we can also be seen."

So it is within this dialectic of seeing and being seen that I want to place my remarks today.

Last week I re-entered the United States after a month of panic over the deportations of academics.

I breezed through immigration at JFK simply by having my face scanned at Global Entry. No passport was handed over. No questions were asked. I had chosen this route as an added layer of security for myself.

I don't advise it for everyone, but it worked for me. Now even three months ago, I would have considered any biometric capture of my face an absolute endangerment to self. Things have changed.

It is no longer possible to imagine an outside to a world of digital surveillance, be it optical or sonic. Most of humanity does not have the privilege of refusing video capture. The watchful camera is everywhere, and to be seen by the camera is quite frankly the price of admission.

When we think about the conditions of our existence today, how to survive in this world, we must ask how we might rethink, reuse, appropriate, and reorient the camera. This is one of the central questions confronted by CAMP over their many long years of collaborative practice, and today I'm going to focus on their most recent work,

Bombay Tilts Down

Bombay Tilts Down

Bombay Tilts Down is an ode to Bombay City, written in a form that the city knows most intuitively through a self-reflexive camera.

Mumbai has a long history of cultural representation. It has been romanticized and berated, disavowed, and embraced again and again in poetry, prose, painting, and most iconically, I think, in cinema.

This is a city that loves the camera, and the camera is irresistibly drawn to it.

Bombay's popular cinema of the long 20th century was hopelessly entangled with the city in a turbulent affair that was quite melodramatic, yes, but also often postmodern, in what I want to call its citational intimacies, it's obsession with it's own archive of images.

And this is just for the fans in the room.

If cinema is an archive of the city, the city too is an archive of cinema.

Bombay Tilts Down

Bombay Tilts Down illustrates this perfectly as the camera looks out at places that are overlaid with cultural memory.

Consider one of the opening sites in the installation, the Haji Ali Dargah, shrine of a 15th century Sufi traveler.

One could view this opening as a cliché of filmic Bombay, laid out in a panoramic view, and yet there is a difference between cliché and citational intimacy.

Soon, a dramatic voice on the soundtrack declares that the city is dead. Another voice calls out, "hartaal", strike. Many of us who have been schooled in Bombay cinema instantly recognize this voice and the citation.

It is Amitabh Bachchan in Coolie. This is when he's saying "hartaal!". There are many playful densities in

Bombay Tilts Down. And you may or may not recall that the film Coolie ends with a climactic, highly overwrought scene shot at the Haji Ali shrine.

So cliché turns into a citational intimacy, a very playful familiarity with the city that is learned through images.

The caption and the credit text in

Bombay Tilts Down tells us that the video was shot from a single point over the duration of two months. What does it mean to shoot from a single point? Does the camera stare fixedly straight ahead, come rain or shine? Far from it.

Camp positions a China-made generic CCTV camera on top of a 35-story building in South Mumbai and tilts it down. What this means is that the body of the camera doesn't physically move, but it swivels up and down and often even pans left and right, but from a single point.

Now the aerial view or the view from the sky has a very long genealogy and many over-determined meanings.

The God's eye view of Judeo-Christian iconography, the all-possessing eye of an anthropocentric Renaissance vision, the panoptic gaze of a carceral modern state, the reconnaissance eye of military intelligence.

So we understand that the view from the sky is one that can see more than humanly possible, and this view grants us perhaps superhuman omniscience, where total seeing is total knowing.

This is a kind of epistemic arrogance, and it is satirized, and I'm going back to another Bombay film from 1983, satirized in the film

Jaane Bhee do Yaro . And these are the annotated versions of the film from CAMP's Indiancine.ma.

Two oily capitalists view Bombay from a construction elevator. They are strategizing about how to clear slums and raise skyscrapers. These slums are located on prime real estate, but they are not visible from the ground.

But from the air, they announce themselves as pure cash.

Main achi hun ghabrao nako.

Main achi hun ghabrao nako.

(How do I go back? Okay, so there was an error).

At the same time, the filmmaker's camera, also positioned in the sky, becomes a tool to expose this greed, an investigative apparatus that can unravel the will to mastery.

The camera is trained on a scene of crime, and it is intent on exposure.

[as WB points out, the crime scene is always deserted. That is, by the time a place turns into a crime scene and is examined, photographed, turned into a forensic laboratory, the crime has been committed, the criminals have vanished, and the investigators clear the space of bystanders to get on with their search for clues.]

Appropriating all that and counter this imagination of exposure, with a counter forensic imagination. Consider Beram, an intrepid detective in a novel written in Bombay in 1927. He is bent on locating the photographer who captured a blasphemous image of the sacred Parsi Tower of Silence from an airplane. Based on a real photographic event, the novel stages the quest for photographic justice as a detective cat and mouse game.

Recursively, Bombay's best self-representations play on this edge of this dialectics between transparency and exposure. The city as a crime scene invites a forensic imagination, one in which we can only reconstruct the crime in its wake, in its aftermath.

For Walter Benjamin, certain photographs expose the city as a scene of crime, initiating a phenomenology of urban space framed as a historical trial. I'm just going to try this again.

So photographs such as this, - this is the famous Atget photograph - that Benjamin talks about, where the city is uncannily empty of people and faces and announces itself as a scene of crime.

The city seen in

Bombay Tilts Down is a crime scene too, but the crime is ongoing and the scene is rather crowded.

The mills are shut and the capitalists are exercising in their terrace gardens.

The tallest building will remain unfinished because it is mired in illegality.

The shrine of the learned Haji can no longer be seen from the road. It is covered over by construction scaffolding. And this is during the pandemic. This is a city that was reclaimed from the ocean by technocrats and bankers, and that hubris might never really lose its grip on Bombay.

The forensic imagination is appropriate for this urban palimpsest. Layers and layers of history and geology. The epic ongoing struggle between land and sea. The waves of migrants and other itinerants.

The unhoused and the underemployed. There is a deep time coded into the spatial landscape and it is much more than human.

CAMP's use of the CCTV camera, however, is not forensic, I'd say, nor is it exactly counter-forensic. Both these concepts and methods have been pushed to their limit in the last two years as we have watched a live stream genocide on our screens.

How much more evidence do we need? What else will the camera uncover? Forensics has a deep faith in the techno-modern, a futurist conviction in the ability of the kino eye to see a verifiable truth. Its genealogy of use has notoriously been in scaffolding carceral regimes, where identification and tagging must precede criminalization and incarceration.

The camera apparatus, the computer software, these are privileged as scientific and objective tools. Is it possible to grab this forensic faith in technology and reverse its case? Can a counter-forensic method avoid the cold clinical investigation of the crime scene that reduces all experience into data?

In a recent issue of the journal World Records, Laliv Melamed and Pooja Rangan interview the Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigative Unit and Rachel Nelson to discuss the tensions between forensics and memory, evidence and testimony.

For Rachel Nelson, technology cannot be accorded primacy over memory. Testimony can never be abandoned. But the problem is not just the tools in themselves, but rather the hierarchization of evidentiary sites and methods.

Bombay is not Gaza, but CAMP has been thinking with Palestine for a very long time. And you got a glimpse of that in Lawrence Liang's presentation. More than a decade ago, Shaina Anand's film,

The Neighbour Before the House, reoriented the CCTV camera to watch the watchers.

Eight Palestinian families in East Jerusalem train a CCTV camera on tourists, on the IDF, on homes that were once theirs.

They speak over the footage, remembering material spaces as palimpsests of memory, now invisible to the camera. And the edited film is at once testimony and evidence, or shall we say annotation and evidence.

Bombay Tilts Down

Bombay Tilts Down does something similar in form. It mixes CCTV vision with decades of revolutionary poetry, popular film references, and romantic song.

The sensorium that emerges is neither forensic nor counter-forensic, but something else. Rachel Nelson suggests that, “art makes it possible to engage the evidence from a position of immersion rather than evaluation.”

Immersion is only possible when an intense sensory environment is produced, and its main address is aesthetic. By aesthetic, I do not mean the pleasurable of the beautiful. I refer instead to the aesthetic as experience, a sensory encounter with a work or object that calls out to you on the basis of formal properties, such as shape and color, sound and scale, as well as the object's history of representation, which conditions what many might suppose would be an immediate sensory response, but it is always already mediated.

Bombay Tilts Down

Bombay Tilts Down is massive as a work and loud. Your body throbs with the beats of the dubstep soundtrack. To stay in that space is to be thrilled and overwhelmed by the sensorial surround. It is immersive, it is embodied, and it is saturated with testimony and all the citation intimacies that I gestured towards.

And that's where I think the artwork escapes the genealogies of the forensic imagination.

Yes, this is a landscape of crime, but listen, there are people here who sing their stories in loud voices.

Main achhi hoon, ghabrao nako I am well, don't worry.

So I was meant to play that very powerful moment, but it's not.

You will, you will watch it tonight.

Now, I just don't want to eat into time ...

Yeah, but it's not...

(Video plays)

Main achhi hoon, ghabrao nako

achhi hoon, ghabrao nako

achhi hoon, ghabrao nako

Thank you for this collective effort here.

Okay. Now, CAMP describes this work as a city symphony, and the invocation of this genealogy is quite striking. The city symphony film of the 1920s emerged at a high moment of avant-garde artistic experimentation, when the lure of the city was still felt as a palpable promise.

The city was technology, and what better way to theorize this than through the camera? If Dziga Vertov took the keener eye into the realm of futurist cyborg vision, Walter Ruttmann invoked the rhythm of factory time and the tempo of modern technological life.

Bombay Tilts Down

Bombay Tilts Down is also edited to the rhythm of the industrial city, where the city awakes to the sound of the siren that calls workers to the mill.