Bharat ki Chhap - Episode 3: The Harappan Civilization

Director: Chandita Mukherjee; Cinematographer: Ranjan Palit

Duration: 00:51:13; Aspect Ratio: 1.366:1; Hue: 19.673; Saturation: 0.108; Lightness: 0.372; Volume: 0.267; Cuts per Minute: 7.126; Words per Minute: 74.894

Summary: This episode discusses the Harappan civilization. Some of the characters travel to Harappan excavation sites – reporting their lifestyles, aspects of city planning and governance, jewellery making and terracota work.

Bharat ki Chhap: Episode 3

National Museum, New Delhi

National Museum, New Delhi

1. Amrita and Shehnaz are rushing through the grand entrance of the NAtional Museum, New Delhi. This is a dreamlike scene because we don’t know too much about the Harappans. There is black dark interior and a few spotlights with Harappan artefacts. We created this so it seems like we are piecing together a story with the little evidence that we have. The first thing we encounter are the faces of the Harappans. We just don’t know - are these real people for whom sculptures have been made? Are they gods and goddess? Are they little dolls and not meant to be sacred objects at all? The close-ups of the actors are in the studio in Bombay. The museum objects were of course shot in the National Museum. In similar lighting we have shot the song “What is a city?” and the commonalities of the Harappan city then and the city today.

Shehnaaz: Hurry, Amrita! The museum closes at five.

Amrita: Today we

must meet the Harappans.

Look!

Who were they?

- We're not sure

- Even so?

- Common people like us?

- Or gods?

- Or rulers?

- Or works of art

- Or toys

We can only guess

At the time when we were shooting this - the Hindutva right had not claimed the Harappans as their own. The Vedic people were their sacred Sanskritic ancestors and anybody before that was uncivilized and tribal.

Come, let's travel

To the first cities of Sindhu

Sing the praises of Ramanathan Maharaj!

Sindhu? Who's this Sindhu?

Who is Sindhu? Who's this Sindhu?

The 5000 year old Sindhu (Indus) civilisation!

Everybody knows

Those were cities – what's a city?

Don't you know?

I know! A city is crowds, a city is hustle

A city is bustle and brick houses

-Is that so? -Oh yes, hustle-bustle

and brick houses. Riches too, and poverty

A city is trade, a city – is – trade, a city is -

-Speak up, then! -Government

A city is markets and water systems

A city is relationships, employment, industries

A city is new thoughts, it makes the mind spin

Spin around and about, round and about

Stop stop stop! Were there such cities even then?

Oh yes, such cities, and better still

Many lie buried yet under field and hill

The more we seek, the deeper we go

If we know where to look, the more shall we know

Come, let's travel

To the first cities of Sindhu

Sing the praises of Ramanathan Maharaj!

Sindhu? Who's this Sindhu?

Who is Sindhu? Who's this Sindhu?

The 5000 year old Sindhu (Indus) civilisation!

Everybody knows

Those were cities – what's a city?

Don't you know?

I know! A city is crowds, a city is hustle

A city is bustle and brick houses

-Is that so? -Oh yes, hustle-bustle

and brick houses. Riches too, and poverty

A city is trade, a city – is – trade, a city is -

-Speak up, then! -Government

A city is markets and water systems

A city is relationships, employment, industries

A city is new thoughts, it makes the mind spin

Spin around and about, round and about

Stop stop stop! Were there such cities even then?

Oh yes, such cities, and better still

Many lie buried yet under field and hill

The more we seek, the deeper we go

If we know where to look, the more shall we know

2. We were talking to Dr. Rao, who is a slightly controversial archaeologist in whose work a lot of people do not agree. Subsequently he became part of the arsenal of the Hindutva right.

It was only in the late 90s with the dominance of Mr. Advani, that suddenly the Harappans too were claimed as their own by the Hindutva brigade..

Dr. Rao was doing this important underwater excavations as part of National Institute of Oceanography Goa project. This institute was the only one with boats, dredgers and trained deep sea drivers. Dr. Rao’s findings were not conclusive because the debris at the bottom of the ocean is piled one on top of the other i.e. the debris was not of any one historical period. But Dr. Rao had the tendency to see some Cuneiform markings on a piece of pottery and relate it to Vishnu or Brahma or other Hindu gods - always linking it up to some greater notion of Hinduism. He had another agenda - to say that the Harappans were the original Brahmins and that they migrated to the South.

This actually causes a kind of problem within the right wing notion of history. The people who they venerated as the Rig Vedic people are then just invaders of the earlier city civilizations that definitely more materially advanced. But at the time we were shooting this, he was the only one doing this underwater archaeology. Even at that point some of the things he was saying were problematic.

Dr Rao, roughly how far did the city extend?

You're in a boat streaking white through the water, and your companion says, “From here to that shore were streets and houses.” How would you feel? I found it strange, and exciting, as Dr S R Rao introduced me this to a sunken Harappan city. A small section of the sunken city remains above water, on Bet Dwaraka island. On disembarking we began to find Harappan signs - leftovers of conches used for making bangles. Also typical perforated pots.

Bet Dwarka, Gujarat

Maitreyi: The ruins of Harappa, discovered in the 1850s also yielded objects like those found at Bet Dwaraka. Archaeologists then were unable to relate those finds to any known culture. Today they can confidently say that these artefacts are Harappan in origin. Their confidence is based on the find made later.

Nissim: Mohenjodaro was discovered 60 years later on the banks of the Indus, and gradually people realised that both cities were centres of an ancient and developed civilisation. This changed our view of the subcontinent's past - we'd assume the Vedic civilisation was oldest.

Mohenjodaro

Maitreyi: Now, over 700 big and small Harappan sites are known, stretching from the Himalayan foothills to the Tapi river in the south, and in the east from the Yamuna's banks to the western Makran coast - approximately 1.5 million sq km.

Knowing its true extent, we cannot limit it to the 'Indus Valley' civilisation. Today it's called the 'Harappan' civilisation.

Nissim: As newer sites are found, our knowledge grows - and new questions arise. A village site was recently found at Nagwada, Gujarat

Excavations were on when Ranjan and Amrita arrived.

4. The maps were drawn for the series, but they were approved by the Survey of India under the Department of Science and Technology.

Nagwada, Gujarat

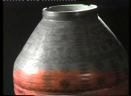

We felt the Mohenjodaro excavation pictures had come to life. A team from Baroda University was at work. The women labourers said the pots found resembled the pots they used in their homes. I noticed some round terracotta objects with ridges. Dr Hegde said these were probably finger imprints. He's named the objects

mushtika.

May I keep this?

Holding a

mushtika in my hand was like shaking hands with an unknown Harappan. Dr Hegde thinks that in some ritual, clay lumps pressed in the palm were dropped into the fire.

3. Amrita visit the University of Baroda - Department of Archaeology. She visits one of the huts in which they have displayed artefacts from their excavations. Interior monologue is one of the formal devices that we have used. She touches and plays with the artefacts. Normally museums don’t allow that, but this was specially allowed for the shooting. She was allowed grind the carnelian on a wet stone, recreating the action of the craft making. This interior monologue always has this charged-up, energetic voice that is not the normal speaking voice, and incomplete thoughts are spoken in phrases, not in sentences.

Am I in a museum or a village home? The same spindle, stove, mortar and pestle, storage jars, beads. Everything's familiar, yet thousands of years old.

Am I in a museum or a village home? The same spindle, stove, mortar and pestle, storage jars, beads. Everything's familiar, yet thousands of years old.

Nagwada, Gujarat

I asked about how those people built their houses. Dr Hegde told me they used sun-dried bricks which were identical in proportion to Harappan baked bricks. Throughout the Harappan civilisation bricks might vary in size but never in proportion. If the height is

1, the breadth would be double i.e. 34 and length double

that, i.e.

4. These, too, are Harappan-type bricks which can be laid in many ways to build a wall. But how to lay them so that the wall withstands stress, and does not fall easily? Let's see how the 'English bond' tackles the problem. Today it's considered the strongest structure and the Harappans, more or less, followed this method. Put the bricks lengthwise in twos in the first layer. The proportion allows us to lay them breadthwise in the second layer. But here next to the two end bricks, we put a brick each of half of width. And so on layer lengthwise and one breadthwise till the wall is completed. This is the English bond - its strength is based on these half-bricks which we placed in every alternative layer

See how, in this wall, the joints are never one above the other. This the stress is evenly distributed and the wall does not easily collapse.

The Harappan masons had understood this principle.

Maitreyi: Contemporary civilisations like Sumer and Egypt also used bricks on a large scale. But these were sun-dried bricks - those regions didn't have enough wood to fuel kilns.

Nissim: A brick is the basic unit of a wall. Walls make houses, houses from a colony. Street connect colonies which together form a city.

Cities can come up haphazardly but Harappan cities were well-planned. All problems – the movement of vehicles and of people, the siting of industries and markets, garbage collection – had to anticipated. Such preconception requires science.

Maitreyi: From the brick to the city, every big and small aspect needs precise planning - as is evident from the Harappan cities.

Such planned cities then existed nowhere else.

Nissim: Cities, to function well, need not only science but social cooperation and sound administration too.

Lothal, Gujarat

Lothal, Gujarat

What? Is

What? Is this

a city?

Yes it is!

Yes, this is

a city!

Yes, yes, this

is a city!

What were they like, our first cities?

These cities, these cities, these cities

Lothal, near present-day Ahmedabad. The best-preserved Harappan city in India, though only the plinths of the house remain. Lothal wasn't as large as Harappa or Kalibangan - it was 6 or 7 hectares, Harappa about 50. Yet certain things were identical, everywhere -

brick proportions, weights and measure, city planning.

Many places had one area that was on a rise - here, probably, lived the rich people. Their houses were large and often two-storeyed. Other sections had smaller houses where the poor lived.

High and low areas, rich and poor - who knows what sort of relationship they had? We know so little about their society, thinking, daily life, religion, politics

They baked agate in this furnace to make carnelian beads. In this section must also have been pottery, copper and cotton cloth industries. Merchants and craftsmen seem to have lived here.

Surkotada, Kutch, Gujarat

On the edge of the Rann of Kutch is Surkotada, small Harappan hamlet. Here stone, rather than brick, meets the eye. Yet it was as well-planned as other Harappan cities.

Such an extensive civilisation – cities, villages, small towns – what bound them together? Each town had its unique features. High walls surround this place – perhaps as a defence against foes. In Mohenjodaro the east-west streets intersect the north-south, forming crossroads with housing plots in between. And in Banawali, the streets radiate out from a point. So many cities of so many kinds!

Lothal, Gujarat

Surkotada, Banawali, Rakhigarhi, Rehmanderi

Mohenjodaro, Lohumjodaro – these cities!

Daimabad was populous, Ganveriwala had rural ties

Rangpur was colorful, Dholavira was fortified!

-Di di di di? -Rozdi!

Ji ji ji ji? -Kot Diji!

-Hurry, hurry? -Aamri!

-What else do you know? - Allahdino, Allahdino!

Come, let's go to Lothal

Courtyards, gardens, Kalibangan!

Big city, Harrapa, little town, Chanhudaro

What were they like, our first cities?

These cities, these cities, these cities

Surkotada, Banawali, Rakhigarhi, Rehmanderi

Mohenjodaro, Lohumjodaro – these cities!

Daimabad was populous, Ganveriwala had rural ties

Rangpur was colorful, Dholavira was fortified!

-Di di di di? -Rozdi!

Ji ji ji ji? -Kot Diji!

-Hurry, hurry? -Aamri!

-What else do you know? - Allahdino, Allahdino!

Come, let's go to Lothal

Courtyards, gardens, Kalibangan!

Big city, Harrapa, little town, Chanhudaro

What were they like, our first cities?

These cities, these cities, these cities

Amrita: The city has a network of drains.

Ranjan: That's part of city planning. Smaller house drains joined the road drains which emptied into the main street drain.

Amrita: Ranjan - these drains show how well natural slopes were used.

Ranjan : In fact, they even

made slopes where needed. And the drains were brick-covered then.

Amrita: To think that for centuries this technique was lost. Why does that happen?

Such an advanced technique – but its maintenance? They must have ensured the cleaning was regular. What sort of government did they have?

Such an advanced technique – but its maintenance? They must have ensured the cleaning was regular. What sort of government did they have?

I read how, while digging, toys were found which children must have lost in the drains!

Toys, and many other things

Were made of clay by those masters of clay

Dolls, bead, bangles, earrings

Oven, stoves, pots and plates

Houses of baked brick adorned the cities

Terracotta reigned supreme in the cities

Toys, and many other things

Were made of clay by those masters of clay

Dolls, bead, bangles, earrings

Oven, stoves, pots and plates

Houses of baked brick adorned the cities

Terracotta reigned supreme in the cities

National Museum, New Delhi

Lothal, Gujarat

This is Lothal's most unique feature. There are many opinions on what this was - but its excavator believes it was among the largest dock complexes in the world. The dock, 400m long and 30m wide, could shelter 25 or 30 boats. These used a canal to and from the Bhogavo river where the ships anchored with goods from West Asia. These hollows must have held a wooden gate which was lowered or raised to control the water level. In the far-flung Harappan trade Lothal must have played an important role. There was a big warehouse close by, where merchants must have stored their goods - beads, grains, perhaps bales of cotton cloth.

What was it like, the inhabited city? When people returned from faraway Sumer - bustle, bargaining, reunions!

What was it like, the inhabited city? When people returned from faraway Sumer - bustle, bargaining, reunions!

This was the Lothal warehouse. Then it caught fire and was razed to the ground. That's how it was, when excavated. Why was it never repaired? Had trade declined? Making them abandon the structure? Or had people begun to leave the city? Were they unhappy? Or oppressed? What was happening in these cities at that time?

This was the Lothal warehouse. Then it caught fire and was razed to the ground. That's how it was, when excavated. Why was it never repaired? Had trade declined? Making them abandon the structure? Or had people begun to leave the city? Were they unhappy? Or oppressed? What was happening in these cities at that time?

National Museum, New Delhi

These big cities with their far-flung commerce must have relied on written records which have not survived. We have found only seals and pots, inscribed with symbols. Historians have long been trying to decipher these. They're yet to reach definite conclusions - but we know it isn't a pictographic script, and it's written from right to left.

National Museum, New Delhi

Shehnaaz: Amrita, it's so puzzling - those people left behind so much, yet each thing

Amrita: Seems to hide a secret?

Shehnaaz: Yes! Once the script is read we'll learn so much about them - and about ourselves.

Amrita: The animals, anyway, are recognisable.

Nissim: The seals have other familiar symbols -

peepal leaves, the

swastika, and, seated in a yogic posture, a figure who is though to resemble Shiva.

Maitreyi: It's also known that merchants used these seals to stamp their goods. Once we understand the script, we may learn the merchant's name, what goods he was carrying, where he came from, where he was going. Or we'll find a prayer for the safety of his goods, or a traveller's plea for state protection. Surely we'll learn something of their business methods, religion, government.

Nissim: The script is unlikely to answer

all these questions. We'll still have to depend on everyday objects and on comparisons with other civilisations of the time, like Sumer and Egypt.

Fields near Allahabad

Like Sumer and Egypt, Harappa was a riverine civilisation, dependent on annual floods, which left fertile soil deposits on the banks. Their crop-growing was based on this cycle

Rabi crops, sown after the monsoon floods receded, were harvested in the spring

They grew some

kharif crops too. Their crop variety makes us think they mustn't have depended wholly on floods. We're now discovering many Harappan sites not on river bank. So they had wells and canals, to contain flood water. Explorations at sites like Allahdino near Karachi show that artesian wells were used for irrigation.

All the evidence suggests that their food consisted of items familiar to us - wheat, barley, millets, sesame, peas. They may have grown cotton, fruits like pomegranate, grapes, dates, bananas, watermelon. What sort of agricultural implements did they use? These must have been mainly of wood, rope, bamboo - materials that perished. Clay objects survived - such as this toy plough found in Banawali.

This gives us some idea of their tools.

National Museum, New Delhi

Banawali Ploughshare

A field in Kalibangan, excavated in the '70s still bore plough-marks made 4000 years ago. In Sind and Rajasthan such grid ploughing is still done. Archaeologists thus know these were plough-marks. In this method, furrows in one direction were closer, while those in the other were further apart. In closer rows they planted a shorter crop and in the further-apart rows, a taller crop. So the tall crop's shadow did not fall on the short, and both got enough sun. Thus the Harappans had analysed the shadow cycle, and accordingly evolved a method of ploughing.

Amrita: Isn't it lovely, Shehnaaz? Was it for storing grain?

Shehnaaz: Here's a farmer, and a pair of bullocks.

National Museum, New Delhi

Look at the range of copper tools they had. But was there enough copper then for everyone to have such tools?

Shehnaaz: Do you recognise her?

Amrita:Who doesn't?

Nissim: We've known the Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro since childhood. Besides being beautiful, she proves the Harappans had learnt to make bronze.

Maitreyi: Bronze is an alloy. Copper is made hard by adding lead, tin or arsenic to it. Copper was in use by the end of the Stone Age in the Indian subcontinent, but Harappans were the first to use bronze - though copper and bronze had long been common in the West Asian region.

Where in India were the copper mines? Ramanathan takes us on a journey.

Khetri Mines; Khetri, Jhunjhunu District, Rajasthan

Analysis of Harappan bronze objects tells us their copper came mainly from the Aravalli hills, from deposits like this, which still yield ore. Today we can extract copper from low-grade ore, but the Harappans needed ore that had a high copper content. The area has many such pits – disused mine shafts, from where the copper came thousands of years ago. This- Hindustan Copper Ltd in Khetri, Rajasthan - is India's biggest unit for extracting and refining copper.

Khetrinagar, Jhunjhunu District, Rajasthan

Potter's kiln firing

At first, there were stone, wood, clay. With metals, everything must have changed. Metal is more malleable, it can be twisted, joined,

heated and beaten into desired shapes, melted down and cast in different moulds. But ore is rock. How was it realised that it could yield metal? Was it through the potter's art - which already used fire to transform materials?

Maitreyi: Potters, to decorate and burnish their pots, must have experimented with a variety of clays. Perhaps some ore got mixed in with the clay and the temperature, air pressure and oxygen in the furnace combined so as to smelt the ore. It may have been a coincidence at first - but no industry can depend on coincidences. A technique that can be understood, and repeated, is needed.

Nissim: Besides copper – and bronze-making, the Harappans were adept in many technologies - cotton cloth, bead-making, boat-building etc.

Maitreyi: Making bangles from conch-shells too. In coastal Nageshwar in the Gulf of Kutch are found bangles in every stage of manufacture.

Nissim: The crafts we spoke of were all local industries, for which the raw material came from specific places. Sometimes it was brought from thousands of kilometres away. Products made of such expensive materials were largely exported, to the Gulf and to Sumer.

Maitreyi: Such large-scale far-flung industries had to have standardised weights and measures. We've found a variety of weights, small and big. These are identical in every region of Harappa. They're on a scale that doubles – one, two, four, eight, sixteen etc.

Nissim: Historians believe that from about 3000 to 1700 BC was Harappa's most prosperous period. There were other cultures in the subcontinent, technologically less developed than Harappa, but there was certainly trade between the two. How else did a Harappan pot and beads reach Burzahom in Kashmir? And gold objects were found in Lothal, but the area has no gold.

National Museum, New Delhi

Lothal Museum, Lothal, Gujarat

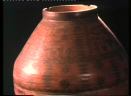

So many kinds of beads! And the colours – red, yellow, blue, purple. Terracotta, stone, copper, gold, every possible material. After a long journey, I reached Khambat - a small coastal town in Gujarat. Here they manufacture agate beads. Agate is baked in furnaces to make carnelian. In this locality, every household is engaged in this industry. Some break the stones, some drill, some polish.

The Museum, Mumbai

National Museum, New Delhi

Khambat, Gujarat

The outer crust is broken with a hammer of horn, because such hammers don't shatter the stone inside. Bow drills are used for making holes. Was the Harappan bead-making technique the same? The agate industry is just one example of links between Harappa and our own times. Perhaps many of our present-day crafts began with Harappa. Who knows?

Maitreyi: Harappan agate beads found in West Asian countries reflect their popularity abroad, then as now. The Harappans must have voyaged there in boats - but how? The stars gave directions, but what instruments did they use to fix their course?

Nissim: All we can say is that they must have sailed along the coast, avoiding strong mid-ocean currents. It was a long voyage from the Gulf of Kutch to Sumer. To carry enough food and water was impossible. On the Makran coast, two small Harappan settlements have been found – Sotka-koh and Sutkagen-dor, where they must have stopped for supplies.

They released birds to find land, as depicted on a seal. Sumer's written records mention a certain land called Meluhha. Its industries, crafts and sailors are highly praised. Historians think Sumerians called the Harrapan area Meluhha.

Arabian Sea, Okha,Jamnagar District, Gujarat

Meluhha, Meluhha – where oh where, was Meluhha?

In Sumerian records

the name of Meluhha shone bright

Meluhha, Meluhha – where oh where, was Meluhha?

In Sumerian records

the name of Meluhha shone bright

We'd decided to complete our reports, meet in Kutch, and travel to Dholavira.

Bhuj, Kutch, Gujarat

Dholavira, Kutch, Gujarat

Ranjan:Once more I realised how our traditions remain alive.

Shehnaaz: Are the Harappan pots found at the site here at all like your own pots?

Potter: Well, our pots are not as sturdy and heavy. But yet the painted motifs are fairly similar.

Archaeologists predict that Dholavira will be the biggest Harappan city site found in India. Though excavations are yet to begin, many artefacts have been found on the surface.

During the '70-'71 famine were building a dam and I was in charge of the muster. As we dug we began to find pots, bangles, etc.

I found a tiny seal I'd no idea what it was - but it matched a picture in a history textbook. I had no use for it, and wondered what I should do. So I took it to Bhuj, to the museum's curator. He said it was very significant and told the newspapers. The publicity brought archaeologists who said this was a major Harappan site.

The mound of Dholavira! Once a prosperous city. Preparations for digging were under way yet our archaeologist-guide found some time for us. The mound's shape, and objects found indicate that this city was divided into three sections. Each section had its own fortification walls. Open spaces separate the high and middle areas. Having shown us around, our guide left us to our own explorations.

With the decline of the Harappan cities their science, too, was lost for many centuries

Why?

Was most of their science controlled by the rulers? So the end of their era meant the end of unique aspects like city planning, standardised bricks and weights? And why did certain things survive - like the copper, bronze and shell bangle industries? Is it that certain aspects of science can flourish only with centralised support?

With the decline of the Harappan cities their science, too, was lost for many centuries

Why?

Was most of their science controlled by the rulers? So the end of their era meant the end of unique aspects like city planning, standardised bricks and weights? And why did certain things survive - like the copper, bronze and shell bangle industries? Is it that certain aspects of science can flourish only with centralised support?

Crafts like these exist even today. 4000 years have gone by. Possibly, the craft stagnated, for it seems their artisans were as poor as ours are today. Those tiny houses in the lower city sections were probably their homes.

Crafts like these exist even today. 4000 years have gone by. Possibly, the craft stagnated, for it seems their artisans were as poor as ours are today. Those tiny houses in the lower city sections were probably their homes.

It's strange how Harappa and Dholavira were both discovered by chance - Harappa when a railway line was being laid and 100 years later, Dholavira in the course of famine relief work. Yet much has changed in these 100 years. When Harappa was found nobody knew where to fit it into our history. But now? The digging is yet to begin, and already we have such expectations of Dholavira!

It's strange how Harappa and Dholavira were both discovered by chance - Harappa when a railway line was being laid and 100 years later, Dholavira in the course of famine relief work. Yet much has changed in these 100 years. When Harappa was found nobody knew where to fit it into our history. But now? The digging is yet to begin, and already we have such expectations of Dholavira!

On the India-Pakistan border is Dholavira. A big centre of trade between Sind and Kutch in its time. Many new artefacts will be unearthed, and we may find answers to some questions that have often puzzled us. Perhaps new questions will arise. Perhaps we will get to know the Harappans better

On the India-Pakistan border is Dholavira. A big centre of trade between Sind and Kutch in its time. Many new artefacts will be unearthed, and we may find answers to some questions that have often puzzled us. Perhaps new questions will arise. Perhaps we will get to know the Harappans better

Pad.ma requires JavaScript.