Bharat ki Chhap - Episode 1: Introduction

Director: Chandita Mukherjee; Cinematographer: Ranjan Palit

Duration: 00:50:43; Aspect Ratio: 1.366:1; Hue: 4.029; Saturation: 0.060; Lightness: 0.361; Volume: 0.213; Cuts per Minute: 5.599; Words per Minute: 76.756

Summary: The episode sets up the intent of the films. We are introduced to the characters and narrators and understand the methods of knowing the past through material evidence. A glimpse of things to come, places to be visited and questions that will be explored are discussed.

Bhart ki Chhap: Episode 1

Humayun's Tomb

New Delhi

1. Chandita Mukherjee annotates Bharat ki Chaap as the main director of the series on the choices and difficulties of making the television series. Inspired by the passage of the Haley’s comet across the cosmos, the series covers the history stretching from the Indus Valley Civilization (Harappa, Mohenjodaro) to the colonial and post-independent period in the Indian subcontinent.

These annotations are compiled from three days of conversations and interview with Chandita Mukherjee. She draws from her extensive knowledge of the history science and technology in India, and also connects to the many changes and developments in India since then. The annotations include some of the details of how BKC was shot and edited, the actors who were part of the series, the political climate of that period. It also includes many stories and histories of science and technology in India that couldn’t be included in the series, and also gives more details and context to the stories that are included in the series, how they were shot, the research behind the series and the scientists, activists and other people interviewed for the series.

Humayun's Tomb; New Delhi

Humayun's Tomb; New Delhi

You're about to see films of an unusual kind. How did it all begin?

Humayun's Tomb; New Delhi

About four years ago Chandita Mukherjee, a young filmmaker came to see me, all excited.

Halley's Comet was soon to appear - science was being much discussed, and many probes sent to explore the comet

She said: "Halley's Comet appears every 76 years. What was happening in our science when it last came? What were people thinking then? And when it came before that, and before that?"

For instance, when this tomb of Humayun was new? It was an exciting idea, to explore India's science and understand how people thought and lived.

So after four years - of meeting many people, travelling all over the country, visiting libraries and museums, talking to archaelogists, scientists and historians - a great deal has been understood and learnt. The outcome is for you to judge.

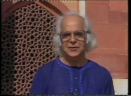

2. Chandita: We were about to go on air and we felt a need that someone accessible should introduce the series to the audience, and say how important it is to explore the history of sciences in India. Professor Yashpal, as a scientist and someone who often spoke simply about sciences to children, was chosen, and he said it very well and convincingly.

There's science, and culture, and fun - but you shall also have to put in some effort.

Young people as well as old should enjoy these films

TV_talking heads

Let me add that seeing these films being made has taught me many things as well.

We hope that films of this type will help in creating a new Indian identity - a truer sense of what we are, who we are

Have we succeeded? Write to us, tell us what you think of this story about ourselves

Comet studio and base office; Mumbai

Comet studio and base office; Mumbai

What is Bharat ki

Chhap?

Chhap sounds like

bidis, or incense sticks but these are thirteen films or a journey that beings with some questions. We'll discuss these later.

3. Actors/Characters in BKC

Along with the television series, BKC also produced a book in Hindi and English to be read along with the series. The BKC book includes written “autobiographies” for the characters in the series. In the series, these characters are drawn to science and history from different backgrounds and interests, often similar to the biography of the actors themselves. Some come from theater and politics, others were historians. Through the characters, we were trying to personalise the grand themes and events that BKC explores.

Here we see the different characters being introduced. We start with Nissim. Played by Hemu Adhikari who was a scientist and biologist at the Bhabha Atomic Research Center. He was also a well-known Marathi Theatre actor. He was seen a lot in Marathi TV serials and features films, some Hindi feature films also. Of course left leaning in his outlook and part of People’s Science Movement. All this was included in his character.

Nissim (Acted by Hemu Adhikari): I’ve always been interested in theatre. On several occassions I have also enacted as historical characters. Somewhere my personal philosophy to life, I think, is linked to my training and work as a historian and as a result I often place problems of a special kind. A young friend of mine saw these films and read parts of the manuscript of this book and making a face said, “Why are you giving so much importance to communalism?” According to him, its just another issue being used by some people just like unemployment is being exploited by drug peddlers and criminals who give work to young unemployed people. So it so happens that most of the articles that he has read are were concerned with issues of communlaism, regionalism, Indian identiyt and so on. But however on reflection, I think that this emphasis has to do with my being a historian.

He continues to be associated with my organization, Comet Media Foundation, and now is currently the treasurer of its trust.

<insert from scans from the book>

First, introductions. I'm Maitreyi, a researcher in computer science. I've also written science books for children. And Nissim teached history at the university. He is also involved with Marathi theatre. Nissim and I will the anchorpeople, but four young reporters will take us on the journey

Then there is Maitreyi. Vasundhara Phadke played the character. She was a chemist by profession and she was working in a commercial company making pigments. She even registered two patents in the name of the company - one is of water soluble wax crayons for children and the other is fluorescent printing ink. People were telling her to pursue a PhD. During this time we met when I was shooting a film on disabled children in Pune. I was to meet the children coming into therapy at a hospital and also go to their homes, meet the parents and observe their other activities. So I needed a Marathi translator - her cousin at the hospital where I was shooting introduced us. We got on really well and she realised she loved the film-making process, but she returned to her job as a chemist. Then when Bharat ki Chhap started, she joined and started working with me. At that time she was an assistant director working on the script and the research. She also started editing for films. And then went on to create material for education.

<Maitreyi scan>

Urmi Juvekar was an aspiring actor and she worked on this project and later went on to become a Hindi film script writer. She brings a great awareness and analytical thinking process to commercial films that sets her apart. She was also a child actor who worked with Sulabha Deshpande’s theatre group. She also acted in Shyam Benegal’s film Yatra.

<Amrita scan>

- I'm Amrita Prasad.

-You're from Calcutta?

We wanted people for a year of research, free to travel all over who'd find the project fun as well as educative. So we met many students and professionals. Finally we did video tests with a dozen people to see how friendly they appeared camera and how confident

“And when people put aside nation, religion, caste...". Thus we selected T. Ramanathan. “Sit and discuss their problems together surely it's because of the impact of science. What, then, is science?”

Jayaram Tatachar was an NSD alumni. A very fine actor - he runs a theatre company in Mysore. He has acted in quite a few Kannada and Malayalam feature films.<T. Ramanathan scan>

Ramanathan has studied psychology and chemistry. For four years he's been correspondent for a science magazine in Madras. He felt this project would give him experience of another kind of journalism.

Amrita Prasad has an MA in comparative literature from Jadavpur University. The youngest reporter, she's studied science only till school, and then she found it very boring! But now she feels her education was incomplete

Comet studio and base office; Mumbai

These people who've agreed to travel about for a year, have they no other work? They do, Aunty, but this too is work! In fact,

I'm the only one straight from university

Shehnaaz is a lecturer in microbiology - she's taken a year's leave from college to do this. Ranjan's a civil engineer, doing his doctorate.

Then there is Anniruddha Limaye. He had an MBA and worked at the Taj. He decided he didn’t want to be a manager anymore. After BKC, he went to make some documentary films. Now he has returned to management.

<Ranjan scan>

Ranjan Pradhan was looking for a break from studies. He felt our project might help him decide what to do next

Comet studio and base office; Mumbai

Shehnaaz Khan lectures in microbiology. She's also active in people's science movement. Maitreyi knows her well. But Shehnaaz is so busy, we never thought she'd join. However, she was thrilled!

Sohaila Kapur was a journalist in the Times of India. She was the assistant editor of Femina. She wanted to start travelling and came on board with us. She now appears on Lok Sabha TV where she moderates a talk show.

<shahnaz scan>

Women developed so many techniques – pottery!

-Yes, and agriculture

– Medicine

But once these began to have an impact, women lost control over them. That's what almost always happens. And not only women, men too are among the losers. The question is, why don't the benefits of technology reach all sections of society? We must keep these issues in mind as we're making films on the history of science.

- Precisely

Then there is Raghu played by Shiv Subramaniam. He is a Bombay English Theatre actor. Subsequent to these series he worked in Bombay commercial cinema.

We used the characters and their questioning to bring out the many connections between history and science. The characters were our device to make our questions and confusions known – Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? We can only shape our future if we know our past… These sort of thoughts are repeated again and again.

This questioning had to be done also because education in the Indian context has been about rote-learning, so the method of the series as questioning received knowledge was not entirely familiar. Since an integrated approach to knowledge doesn’t exist in our society and certainly didn’t thirty years ago, we really struggled to establish these connections between our roots, who we are and the future. The metaphor of a journey metaphor is another important part of the form of BKC. It in fact borrows from other books about science; Jules Verne did it in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, and there have been others too. These journeys are about the protagonist getting shaped by the journey, connecting things and gaining knowledge along the way.

Comet studio and base office; Mumbai

We were discussing our title. Simply put, these are films about our history and we particularly want to know what was happening in science in different ages.

3 (continued). The series projects back on the history of science and technology, but as the title suggests the idea of ‘Bharat’ was taken as a given. We didn’t think of this as a strategy at the time. People with a general commitment for the left and making the world a more equitable place, were simpler (or less critical) in their formulations and they thought also that things would change in the country. And that didn’t happen. The idea of class struggle and so on were perhaps naïve and uni-dimensional, not taking into account many other aspects of society.

We thought then “expose the godman and the godman is dead”. But it doesn’t happen like that. This kind of nationalism that you see in BKC is part of that same naiveté and simple-ness. Things have changed a lot since then, but I wouldn’t say that I have become cynical. I still think it’s possible for the world to change.

For we want to understand - Where have we Indians come from? How did we get here? Where do we want to go, and where are we going? What are those signs by which we're known? Who are we? So it's a question of our identity, therefore,

chhap, or imprint

This search will take us to many places and many ages. We'll sing, too, when we feel like it! And talk of things that concern us all.

We hope these films will help us talk to as many people as possible

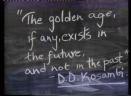

3 (continued). One thing that the history of science shows us is that whether its communalism or patriarchy or racism science cannot alone do anything to anything to tackle these issues. Science can infact be moulded and used by a tool by such forces as in NAzi Germany or as reflected by the image of women created by modern socio-biology or in the racism that is latent in all of the 19th century European biology. So history shows that unless science aligns with progressive trends in society it cannot become an instrument of liberation, in fact it can act to the contrary. The biggest impediment to the study of history has been the sectarian outlook of historians - be it the history of society or the history of science.

As makers of the series, we were aware of the different positions around science and used the characters to portray these – those who align scientific thinking with progressive thinking, those who are obsessed with India’s contribution to science, and so on. For instance, the character Amrita (played by Urmi Juvekar) is obsessed with Indian identity and sciences.

In the BKC book, the essays by the six characters is the journey they take after the series ends.

History is obviously related to the present. Especially in India, where so much in our society has its roots in the past. So it should be clear that to know our present we must understand our past or we'll be stepping into the future blindfolded. Already, there are blindfolds over our eyes that we have to remove one by one

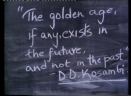

5. We have to remove the blindfold by knowing our past - this is the stated ideology. It does seem pedagogic now, which is a mode that is no longer popular.

Thus our interest in history. But why science? What role has it played in shaping us? For one, the kind of research done in Europe on the history of science has not been done here. This creates the impression that we have had nothing to do with science. As a result, some western scholars, and many of us, too, believe that India was and is a great 'spiritual' nation, and we're even proud of this 'heritage'.

But this picture is incomplete, and false. We believe enquiries into our scientific past will bring us closer to the truth.

4.We needed characters who were just people struggling, researching, exploring along with us who were making the series. It came together all at once we need these characters rather than people who knew it all, like scientists and experts. They had a range of backgrounds - one is historian, someone is a Computer Engineer, and they keep asking each other questions and growing together as the series progresses. There was a lot of discussion about whether to have it based on themes or in linear progression. We also decided to make a montage of different forms so acting, singing, dancing and folk forms being performed by people in the place we went to.

We used visuals drawn from the architectural monuments we visited, like the figurines in Sanchi railing. This is where we found the story of Jeevak. Similarly we used all the visual sources that were emanating from all the historical stuff we were reading and understanding. We decided to have a song in every episode in different costumes. (We even have a song of the songs - that tells the history of science in India in song format.) Sometimes stylised and sometimes not, sometime speaking in the Brechtian style, sometimes we used various folk forms like Lavani, Garba as well. We thought we would do a lot of animation but it was expensive and cumbersome in those days.

Many think of science as a modern, western phenomenon. But science has always been present, everywhere. As when humans learned to make fire, to domesticate wild animals, to build houses of bricks.

6. Around the same time, Shyam Benegal’s Bharat Ek Khoj was also telecast, and the names sound similar which often confused by people to this day. But these are actually different works. There was also Mahabharata on TV on at the same time.

In retrospect one realizes that the Mahabharat telecast then with the script penned by Rahi Masoom Raza was well written and superior to the version produced now.

But it was the telecast of Ramayana and Mahabharata on TV in the late 80s that fuelled Hindutva. It was effectively used to create popular support because these tales were retold in a graphic and extended fashion and fueled communal feelings. I wouldn’t say the makers were thinking like that but this could be the impact it had…

Returning to the similarity to Bharat Ek Khoj and BKC, Benegal also used dramatization and quoted from famous works of literature but the scale of that series is totally different. His series was big budget, big actors, actual sets, and ours was relatively low budget. BKC stretched out for 4-5 years but in total cost about 104 lakhs (1,04,00,000 INR or over 1 crore). Even in those days this was unthinkable. The wage was 100 rupees a day for everyone on set including me. The crew really did it for the fun and experience of it, for an experience that would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

Whenever I meet any of the people involved, they all say that watching the series as a whole was very important for them. A milestone.

Advances in science were made here, as elsewhere, but to what extent? It's a popular misconception that from the start, our

shastras have contained all the scientific knowledge in the world. But such claims are without proof. The ancients imagine many things that give rise to legends, which are part of us. But if we believe that thousands of years ago our ancestors had airplanes and atom bombs, this results in false notions about ourselves. We find no remains of such things

Instead, evidence reveals that 6 – 7,000 years ago, people here lived by hunting and gathering food. Here, too, they learned to make stone tools, and to use fire. Thus science and technology moved ahead.

That was the Stone Age, the start of our journey through the Indus civilization, the Vedic age, the Deccan caves and southern states,

the exchange with the Arab world and the coming of the Afghans and Turks, the Mughal period and the British

raj,

to the present. We'll see how medicine, astronomy, mathematics grew and observe the techniques of craftsmen. This time, we'll give you an idea of our methods

9. This is not to say that there wasn’t anti-national discourse at the time. The emergency had happened almost ten or more years before, but news of the atrocities in Nagaland and Kashmir and other places were not yet so much a part of the general discourse.

People who were part of progressive circles and also through news, generally it was known that incidents were taking place, such as attacks on people in Bastar, attacks on Dalit people, villages and hamlets. Though the direct linkage of the State to these was probably not so visible at that time. We were not so naive to think that the State was great!

I don’t think you should mistake that nationalism in BKC for Stateism. And another criticism that people sometimes make is that “Oh you are supporting monumentalist science!”. I don’t think so. We are not saying that the Bhakra Dam is the greatest thing in history. We are quite critical of things that cause damage to the environment and cause inequity among people, such as driving tribal people out of their homelands. There is criticism of some of these projects in the series.

We also did not have to deal with as much direction and censorship. This sponsor driven script that is so common now was not the case in the circumstances in which this project was funded. Although the sponsors were Department of Science and Technology, officials weren’t coming and checking the script before shooting.

This was perhaps unique to BKC, unlike other programs that were produced for the Information and Broadcasting Ministry. There they would check on everything from script to production. Department of Space Technology is a research based organisation where people are funded to try out things. It was Dr. Narasimha Roddam who once said to me we build iron walls so that within those iron walls you can play; that they will explain to the members of Parliament and the Government that this playpen is necessary otherwise no ideas will come. It was that kind of respect for experimentation which went into conceiving and producing BKC.

Multiple locations

Multiple locations

10. BKC had an advisory committee headed by Professor Yashpal, including Irfan Habib, Asiya Siddiqui and the then Director of Doordarshan at the time (they would change). We would read our scripts to them. They would advise us on exploring more things and understanding subjects in depth but no censoring on their end.

Let's all go together on this journey of discovery

And bring alive past ages, bring them alive

Let's all go together on this journey of discovery

The road is long and difficult

Unfamiliar, unknown

Mystery and thrills, new experiences

Let's pause at each experience

Knowledge and science grew, society wore new colours

As the times changed each turn was new

Let's pause at every turn

A little hope, curiosity, imagination, interest

These are the means but the thoughts are new

Let's pause at every thought

Let's all go together on this journey of discovery

Let's all go together on this journey of discovery

And bring alive past ages, bring them alive

Let's all go together on this journey of discovery

The road is long and difficult

Unfamiliar, unknown

Mystery and thrills, new experiences

Let's pause at each experience

Knowledge and science grew, society wore new colours

As the times changed each turn was new

Let's pause at every turn

A little hope, curiosity, imagination, interest

These are the means but the thoughts are new

Let's pause at every thought

Let's all go together on this journey of discovery

11.The songs were evolved in group discussions. The people who wrote the lyrics of the songs were Rana Sahri, A.V. Ramamurthy and Prakash Hindustani. They gave shape to the lyrics shape, the wordplay and the fun comes from them. Smriti, of course was very important in writing the songs. She does all the rhymes that are in the English subtitles.

Comet studio and base office; Mumbai

So we all want to bring the past alive. But how? Today newspapers and books record all that happens, all that people do or think, but written records grow rarer as we go back in time.

Yet every age, generation, society, leaves marks - bits of pottery, bones, toys, huge temples too. Many such things are found buried in the ground. Take the recent excavations at Inamgaon, near Pune. Ranjan and Shehnaaz will show us how people there lived, 3,000 years ago

Many ways of determining the age of objects found in excavations are known to modern science. The commonest is radiocarbon dating

We'll learn its principle and see how it's done. Methods like excavating or carbon-dating are useful even where written records exist. How else do we tell whether the records are truthful?

We spoke, earlier, of our identity, of the links between past and present. We all have mental images of the past, however hazy

Often, these are a mix of history and legend

My name is Amrita Prasad. I've always been intrigues by the relationship between legends and reality. While doing my Masters in comparative literature, I read mythological tales from many countries. Questions arose – about their origins, about how much was true, how much poetic imagination. Did the Lanka war with monkey brigade helping Rama really occur? Or did a poet perceive larger issues of his time in a tiny battle and exaggerate the event? Where does one find the answers?

Allahabad fort; Allahabad

12. Amrita talks about myth and reality, and this is a running thread that she pursues through the series. As a student of literature, she looks for the connections in the literary texts and in the archaeological records.

13. The series often overlaps with mythological accounts but no one objected to our use of the texts Ramayana and Mahabharat, or other texts. We never denigrated any of the myths and legends. We have really tried to see the basis on which these stories are created. We see the pottery from the small hamlet of Ayodhya, not the luxurious standards we are made to imagine from the myths.

13. The series often overlaps with mythological accounts but no one objected to our use of the texts Ramayana and Mahabharat, or other texts. We never denigrated any of the myths and legends. We have really tried to see the basis on which these stories are created. We see the pottery from the small hamlet of Ayodhya, not the luxurious standards we are made to imagine from the myths.

Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla; Shimla

Ramanathan had read an article about excavations by Prof B B Lal at places mentioned in the epics. We went to meet him at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla.

Amrita: How did you decide where to dig?

Prof: Places mentioned in the

Ramayana and the

Mahabharata still have the same names, and the same locations as in the epics. The

Mahabharata says that Hastinapur, the Kaurava capital, was on the banks of the Ganga. Today's Hastinapur is also on the banks of the Ganga! Mathura, Kurukshetra and other places associated with the

Mahabahrata have also had these names for generations. So the selection of sites to dig at was simple. Similarly for the

Ramayana. In the story, King Dashrath's capital, Ayodhya, was on the banks of the Saryu, where it is today. When Rama was banished, he crossed there rivers and reached Shringaverpur. Here Guha, the Nishad chief, ferried him across the Ganga. From here he went to Bhardwaj Ashram then across the Jamuna to Chitrakoot.

Amrita: What did you find when you dug at these sites?

Prof: Exacavations at the

Mahabharata sites revealed, in the lowest levels, the remnants of a particular culture, a typical grey pottery painted with black motifs.

A:May I see?

Prof:Certainly!

At the National Museum in Delhi we were to see more examples of this pottery. Every ancient civilization has its characteristic pottery. Pottery finds in digs thus help us know the age of other objects found alongside.

Prof Lal told us that the oldest objects found at

Mahabharata sites go back to 900 BC.

Amrita: How did you date the

Ramayana sites?

Prof: Come, let me show you.

A: His tabletop display showed the place where each object was found, and in which level of excavation.

The oldest finds at Ayodhya were bits of polished black pottery. There were no signs of habitation below this.

At Bhardwaj Ashram, he found Gupta period artefacts. Below these, nothing, till 700 BC. Then the same black pottery. Again, below that, no habitation.

Only Shringaverpur had signs of habitation prior to 700 BC, marked by crude pottery. Thus it was proved that the oldest common level of habitation at these sites was 700BC.

Prof: Clearly, then, the events of the

Ramayana cannot be older than that.

Ramanathan: I have a question, Prof Lal

Prof: Yes?

Ramanathan: Your proofs show that even in the events of the epics really took place the

Mahabharata sites are older than the

Ramayana sites. But tradition claims that Rama was earlier than Krishna!

Prof: Well, tradition says Rama belongs to the

treta age, and Krishna to the

dvapar age - with lakhs of years intervening. But archaeological proofs show that none of this could have happened more than 3,000 years ago.

Amrita: Yet people don't easily accept ideas contrary to their religious beliefs. Were most people convinced?

Prof: Many were. To them, their faith was a thing apart from history. Some people still don't agree, but the proofs are sold and unambiguous - how can they be ignored?

Inamgaon, Shirur Taluka, Pune District, Maharashtra

14. Bastar is an important region that we look at especially in the beginning part of the BKC series. Bastar had not seen any kind of industrialisation, there were no roads or highways or telephone lines. In some remote parts of Bastar they live as they would have 500-600 years ago. People were so confident in their culture. The money economy had not taken over at all.

I'm Ranjan Pradhan, at Inamgaon near Pune. Archaeologists from Deccan College have been excavating here for some years. On this spot stood a circular hut. The artefacts found here are 2,500 years old. And this is only the topmost level. Analysis of these objects helps us know more about those people. Archaeologists are trying to reconstruct what these huts looked like. These holes must have held wooden posts.

15. We were on average 20-25 people on each trip. In 1985, we started writing on the research, then in March 1986 we were given an ultimatum by our funders to show work.

We went and shot a version of Episode 3 (Harappan Civilization) and Episode 1 (The introduction). We had to get it pre-tested. Dr.S.R. Joshi from ISRO went around the country, showed it to students and interviewed them. Their report was to be kept in mind when making further episodes. One of the recommendations of Dr. Joshi was to make half hour episodes - it will be lighter and easier to grasp. The team was against that and continued with 50 minute episodes.

There was also a lot of decision to chapterise the series, how would we divide it? Initially we divided it by topics like Agriculture, Transport, etc. Some things would be reiterated and would be a kind of swimming across of 7000 years of history. But it was all too much to encompass in thirteen overarching themes and it was decided that it was better to go by time period.

So the rest of 1986 we worked on getting the two episodes ready, with pre-testing and getting further with the script. By December of 1986 we went and shot Episode 2 and 4. Then in 1987 we did episode 5,6 and 7. Then in 1988, we did Episode 8, 9, 10. And then broadcast time was approaching in April of 1989. And it was the January of ‘89 and in a mad dash we finished Episode 11, 12 and 13. After that we gave it a bit of a break. This is when moved out of Nehru Centre to the office on Lamington Road.

Many animal bones have been found – cow, goat, blackbuck, sambar, deer. So these people lived in small, circular huts and ate meat – that is all we might have known about Inamgaon, if they hadn't dug deeper.

16. Language: We already had done it in Hindi, and subtitles were in English and we went on to do 7 more language versions – Gujarati, Marathi, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam. This meant dubbing of all the 6 characters and songs had to be written and recorded in all languages. And we had to find singers to match the actors. That went on till 1994. So in all about 8-9 years went into doing language versions as well.

As they dug older levels of habitation were uncovered going back to some thirty generations, or 700 years, before the time of the circular huts. The remains of a wall show that these houses were big and rectangular.

17. The crew would be 4 actors, cameraperson, their assistants, sound person, lighting crew with 3-4 lightboys, along with us on the scripting and direction side. It would be about 20-22 people, if some experts were coming along with us. We tried to use the winter months for travel and outdoor work and the summer months for indoor shooting and editing. The work process had to be convivial. The trips would last 60-70 days at times and we travelled all over, since all the episodes had to have a pan-India character. Many episodes had developments happening simultaneously across country.

We would try to economize by shooting parts of future episodes on one trip. Much of the anticipatory shots are just long shots. Dramatized scenes have to be intensely in their own flow of the particular episode.

-What have you found?

-Some beads

The excavations revealed that in those 700 years, life at Inamgaon had changed considerably. The objects found here might tell us how.

Inamgaon, Shirur Taluka, Pune District, Maharashtra

I'm Shehnaaz Khan, at Deccan College, Pune. This model is based on the find at Inamgaon. Ranjan showed you this topmost level which was 2,500 years old. The huts of that period probably looked like this.

Life in the earlier levels was quite different. These long, rectangular houses had many rooms, whose inhabitants have left behind things that give us glimpses into their lives.

Grains of wheat, barley,

moong, peas, gram, and well-made pottery. The people who made such fine pots must have been fairly prosperous. Such fine craftsmanship and good agriculture! What led it to decline?

Deccan College, Pune

Shehnaaz: Ranjan and I met Prof M K Dhavalikar of Deccan College, who excavated Inamgaon.

Ranjan: Why did agriculture in Inamgaon decline?

Prof. Dhavalikar: Around 1,000 BC, the world climate was changing. Europe has an ice age. And when the polar regions freeze over, there is drought in our part of the world, as evaporation from the oceans goes down.

Shehnaaz: Affecting the rain cycle! So Inamgaon, too, must have faced drought?

Prof. Dhavalikar: Yes, and the drought led many to migrate southwards, in search of better climates. But the people of Inamgaon stayed on, learning to adapt to the new environment - as you saw at the site.

Ranjan: But why did their houses go from rectangular to round?

Prof. Dhavalikar: As the climate changed people must gradually have realised that circular huts withstood the strong winds better. Even today, in places like Rajasthan which have higher velocity winds people build circular huts, so that the winds are deflected around the circular shape.

The commonest method of finding out the age of excavate objects is radiocarbon dating. Only the remains of living can be carbon-dated -wood, bones, charred grains etc. Objects found alongside – pots, beads, tools, cannot be carbon-dated as they non-living.

Carbon is basic to all life on earth - part of micro-organisms, humans, plants. Carbon has two isotopes - Carbon 12 and Carbon 14. C14 is radioactive and there is much less of it than C12. In every living thing, C12 and C14 exist in a fixed ratio. The exchange of carbon with the atmosphere keeps this radio constant. When an organism dies, the exchange of carbon ceases. Will the C12 to C14 ratio remain the same? No

C14, like all radioactive substances, diminishes at a fixed rate while C12 is constant. The number of C14 atoms in any substance is halved every 5,730 years, and further halved after another 5,730 years. This time span is known as the half-life of C14. And as this is neither lakhs of years long nor a few mintues brief, it is ideal for dating excavated objects.

Thus, compared to the bone of a living creature, a dug-up bone will have fewer C14 atoms, and these atoms can be counted. We know the ratio of C12 to C14 in living organisms. This ratio will vary in the dug-up bone and that is how we can tell its age. Thus we can date not only bones, but the remains of all living organisms, such as grains etc. And from the age of these remains, we can infer the age of other objects found alongside.

Recently Shehnaaz went to Ahmedabad where, at the Physical Research Laboratory, radiocarbon dating is done. She met Prof D P Agrawal.

Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad; Ahmedabad

Radiocarbon dating is very simple in principle, but requires care. The problems begin as soon as the sample is found, while digging. If we find, say, a piece of wood, or coal, it could be contaminated by carbon from some present-day source. And then we would be counting the wrong atoms. So the sample is first cleaned by hand, and then the other chemical processes follow.

Dr. Agarwal: This sample is from the ancient copper mines in Khetri.

Shehnaaz: What is the significance?

Dr. Agarwal: We used to think the mines were just 400 years old - the problem was, where did the Indus Valley people get their copper from? We assumed they were using the same copper, but we had no proof. Now for the first time we'll know whether these mines go back to the Indus Vallery period

Dr Agarwal: Now our sample's in the counter – let's check.

Shehnaaz: Can you guess its age?

Dr Agarwal: We need forty hours for an accurate figure, but a few minutes can give us a rough estimate. It seem to be more than 3,000 years old.

Shehnaaz: So it goes back to Harappan times?

Dr Agarwal: Well, it could, but we'll have to wait and see!

Shehnaaz: Won't Ranjan's parents be fed up with our noise?

Maitreyi: They're not in Bombay, I think. 1407 – this way. Where are Nissim and Amrita?

Ranjan: They should be here any minute now

Shehnaaz: Mmm... what's cooking?

Ranjan: You'll see!

photo reference

The episode sets up the intent of the series. We are introduced to the characters and narrators and understand the methods of knowing the past through material evidence. A glimpse of things to come, places to be visited and questions that will be explored are discussed.

Amrita: The others must be here?

Nissim: Perhaps. Are your photographs in here?

Amrita: Yes, and I bought that road map yesterday.

Ranjan: I've seen Inamgaon-type round huts in Kutch too.

Maitreyi: Isn't the climate similar, with strong winds? Actually, so many techniques still survive. They can tell us how people worked, ate, lived.

Shehnaaz: We can keep that in mind as we travel all over. For example, so much in the daily lives of tribals has not changed since the Stone Age. As in the Northeast. Those are Tripura pictures.

Nissim: Very nice

Shehnaaz: Or we could go to Bastar...

Shehnaaz: ... where, even today, it's the women who gather food from the forests. That's how women all over the world are supposed to have discovered agriculture.

Ranjan: Isn't it somewhere in Bastar that they practise an old iron-smelting technique? We should explore that.

Amrita: Besides techniques, sciences like ayurveda still survive. We should try and visit an ayurvedic hospital.

Maitreyi: Ranjan, hadn't you gone to Pune again? How was it?

Ranjan: Quite interesting. The best part was that someone at Deccan College can make stone tools!

Amrita: So we'll travel all over India!

Ranjan: Kashmir to Kanyakumari!

Nissim: And on your journeys you can talk to people everywhere and ask them what they know of history and what their everyday problems are. Instead of viewing history as apart from the present, we can look for links with today's situation.

Amrita: So we'll talk not only to experts, but others too.

Ranjan: But how do we meet people from past? How to present the Harappan age?

Nissim: We can't go to Harappa or Mohenjodaro, but photographs of excavations surely exist?

photo reference

The episode sets up the intent of the series. We are introduced to the characters and narrators and understand the methods of knowing the past through material evidence. A glimpse of things to come, places to be visited and questions that will be explored are discussed.

Maitreyi: And we can go to Lothal and Kalibangan

Shehnaaz: Museums! They must contain objects from every period. They can tell us so much.

Amrita: Looking at museum objects, we can use our imagination. And when we reach the age of ancient manuscripts, we can enact stories from them!

Ranjan: I leave acting to the rest of you – count me out!

The

Arthashastra, Manusmriti, Jataka tales old manuscripts exist in some libraries like the Saraswathi Mahal Library in Thanjavur.

Amrita: What's that temple in Thanjavur?

Shehnaaz: Brihadeshwara

Ranjan: When we come to architecture that could be an example of the southern style.

Maitreyi: Later we can show how the arch and dome revived our stagnant architecture.

Ranjan: The Gol Gumbaz, the Fatehpur Sikri, are as much expressions of our culture as Sanchi or Konarak.

Nissim: We'll see many occasions to speak of unity. We can emphasis that Tipu Sultan was one of our first nationalists.

Ranjan: But how is all this related to science?

Shehnaaz: Of course it is! If we look at our history this way, it may dispel some misconceptions.

Maitreyi: And the way people think is directly linked to science. Take Buddhism - it had such an impact that trade grew, society became more open. Medicine was taught at universities like Nalanda. This atmosphere helped science.

Nissim: But in a society full of discrimination and restrictions, to ask questions or think in new ways is difficult. And, in our past, this has often been the case. That reminds me! I got a letter from Ramanathan.

Shehnaaz: When does he return?

Nissim: In a week or two

Comet studio and base office; Mumbai

It's from Guwahati. He writes -

My tour with the enivornment study group is almost over. We've been to many areas, met many people. Remember the day all of us talked of science as a medium that could change our thinking? That if science reached every home, superstition would end, ideas of democracy take root? But I've seen ... how, even if lives are changing, ways of thinking do not. Development schemes rarely touch the heart or mind. The benefits of technology, where visible – electricity, or new seeds or irrigation – are like things given without asking people what they want. And the people feel they have no right to say whether a given scheme will benefit or harm them. When we raise such issues, we get the same reply - ”Sir, you tell us. What can we say?” We say it concerns them, they should discuss things. They say they have no such tradition – it's all fate

Ranjan: Who decides what tradition is? People say

sati is a tradition, don't criticize it. Caste and untouchability are traditions. But these 'traditions' were started by people like us, after all.

Shehnaaz: And we can choose what traditions to keep, what to leave behind.

Maitreyi: Yes, we're not denying our history. There's much to be proud of.

Amrita: The work of scientists like Aryabhata, Bhaskara, then ayurveda.

Shehnaaz: The craft of our potters, sculptors and weavers

Ranjan: The famers who grew such a range of crops!

Nissim: So we'll keep an open mind - We'll speak with pride or be critical, as necessary.

Amrita: “The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth!” But truly we believe such odd things! I was in a taxi chatting with the driver about the country, science. He said, “What's the use of computers? Life was better in the old days"

In our country, in the time of the rishi-saints, rivers flowed with milk. But today? So many died in Bhopal. What sort of age is this? Milk and

ghee were cheap in the old days. People were so happy!

18.

Q: Do you think that the scientific mode of thinking that DST afforded with what you called the “playpen” - where you did things pre-testing, where you were experimenting? Do you think you absorbed their ways of working? Did it perhaps shape your methods of film-making?

Today there is no limit to shooting of video imagery. We were very limited to the medium of celluloid. We couldn’t just keep on exploring something that was interesting. That method of working with celluloid female necessitated a kind of deliberateness that is not required today. We certainly couldn’t do then do the kind of animations we do today very routinely.

Nissim: True, milk is expensive, there are many problems. I'm sure he reads the paper, watches TV - he knows about today, but is confused about history.

Shehnaaz: An event like Bhopal makes him condemn technology.

Maitreyi: Granted these are troubled times. But if we wish to change things, we must first know the truth. How else can we lay the basis of our future?

Ranjan: Take social reformers of the nineteenth century, or Gandhi and Bhagat Singh in the twentieth century. They stressed the need to know the truth, read history, tried to understand their times. Abolish

sati, prevent child marriages -

Shehnaaz: Allow widow remarriage!

Maitreyi: Give women the right to education!

Amrita: Treat the 'untouchables' as people of God!

Nissim: Quit India! These slogans didn't work on their own. Those who desired reform took pains to comprehend and explain their culture and history.

Gorai Beach, Mumbai

We aren't reformers, we're just making films - and films can't really change the world! But in talking of the past we'll insist on proofs and we'll ask not only

what happened in science or history, but also

how and

why. That is the method of science!

Pad.ma requires JavaScript.