Memory Drawing: Nikhil Chopra

Duration: 01:31:40; Aspect Ratio: 1.333:1; Hue: 163.842; Saturation: 0.093; Lightness: 0.553; Volume: 0.218; Cuts per Minute: 4.428; Words per Minute: 98.078

Summary: Spread over a year (2010-2011) with one lecture a month, the CoLab-Goethe visual art series focused on practitioners who look at both ‘reconstruction’ and the ‘historical turn’ from the perspective of contemporary artistic practice: the revisions and re-readings that take place when images, works or events from the past circulate in a changing set of configurations; the lectures on architecture attempt to look at the radical shift in the imagining of the public space and the notion of spatial equity, and the questions thus raised.

Nikhil Chopra studied at the M.S. University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda for two years between 1997 and 1999. He completed his BFA from the Maryland Institute, College of Arts, Baltimore in 2001, and his M.FA in Painting from the Ohio State University in 2003. Nikhil returned to India in 2005, and currently lives and works in Bombay. Nikhil's practice has been described as located in the border region between theatre, performance, painting, photography and sculpture. As a performer whose practice emerges from the visual arts, the costumes, the selection and installation of props are of great importance, and they also provide clues to the world conjured up by the characters. It was when he was studying in Ohio in 2002 that he first developed his character of Sir Raja. The characters of his performances, Sir Raja, Yog Raj Chitrakar, and the most recently staged Drum Soloist are all semi-autobiographical. And, speaking about his work, Nikhil himself says, "My performances may be seen as a form of storytelling that intermingles familial histories, personal narrative and everyday life. The process of performing is a means to access, excavate, extract and present them. Autobiography is one place I know where to begin from". So, each performance unfolds in a long durational happening done over the course of one day, or several, in slow deliberated ritualised movements. While performing, Nikhil makes drawings that take on new functions and meanings, depending on the site and location. These locations are many and extend worldwide. The Yog Chitrakar Memory Drawings, the series itself, began at the Khoj workshops, and has travelled since to the cities of Oslo, Tokyo, Yokohama, Brusssels, Venice, New York City, Chicago, London, Manchester, Mumbai, Delhi, Srinagar.

Nikhil speaks about his practice, which intertwines personal history and the histories of India's colonial past in live performance and charcoal drawings.

Welcome to our lecture series on Practices in Contemporary Art and Architecture, which CoLab which is basically Suman and Edgar, who is not here today, and the Goethe-Institut have organised together. And for us, it's half-time like in a football match, 6 then have guns, 6 to go, and so far, I think we had a really nice going and we are extremely interested to see what Nikhil is going to talk to us today because when we had both discussed, it's quite difficult to talk about performance. It's difficult to talk about your art but performance is usually something you have to see, you have to witness. So, I am especially interested to see how Nikhil is going to present what he's actually doing. Thank you.

And many thanks to Nikhil Chopra who accepted our invitation to come to Bangalore in spite of his really very busy schedule. He had an important event two days ago in Bombay and is leaving for Berlin on March 7th for a year, so we're really grateful that he made it this time to come to Bangalore, and in spite of his bad throat. This is, like everyone said, the 6th in our series of the CoLab-Goethe Lectures whose theme is loosely based on the idea of representing histories. We have invited curators who have repositioned works from the past and placed them in the new framework of interpretation, and artists who have used contested places, moments and events from the past to make complex aesthetic works. The series was flagged off in July by Roger Buergel, Curator of Documenta 12, and then we had N.S. Harsha, an artist from Mysore, who spoke about his artistic evolution, Nilima Sheikh who talked about her series, 'Every Night Put Kashmir in Your Dreams', and Hito Steyerl, academic and film-maker from Germany, in her artist's talk, spoke about her interest in the history of objects, places and events. Last month, the eminent architect and academic, B.V. Doshi, had a large audience listening to his presentation, 'Revitalising Rural and Urban Galaxies'.

Today, we are delighted to have Nikhil speak about his practice, because he intertwines his personal history and the histories of India's colonial past in his live performances and charcoal drawings. I first came across Nikhil's work in 2008 at the Serpentine Gallery in London during the Indian Highway Exhibition. Nikhil had done a well-known series, the Yog Raj Chitrakar performances, and it was at one of these performances that I first saw him. It was a freezing cold windy night in December and I think it was -7 degrees or something, and I saw Nikhil sitting in a tent in Hyde Park by himself, opposite the Gallery, making large-scale charcoal drawings. I was struck by the endurance in executing this project.

Drum Soloist

Yog Raj Chitrakar

Okay, to tell you a little bit about Nikhil. He has a Visual Arts background. He studied at the M.S. University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda for two years between 1997 and 1999. He completed his BFA from the Maryland Institute, College of Arts, Baltimore in 2001, his M.FA in Painting from the Ohio State University in 2003. Nikhil returned to India in 2005, and currently lives and works in Bombay. Nikhil's practice has been described as located in the border region between theatre, performance, painting, photography and sculpture. As a performer whose practice emerges from the visual arts, the costumes, the selection and installation of props are of great importance, and I think they also provide clues to the world conjured up by the characters. It was when he was studying in Ohio in 2002 that he first developed his character of Sir Raja. The characters of his performances, Sir Raja, Yog Raj Chitrakar, and the most recently staged Drum Soloist are all semi-autobiographical. And, speaking about his work, Nikhil himself says, "My performances may be seen as a form of storytelling that intermingles familial histories, personal narrative and everyday life. The process of performing is a means to access, excavate, extract and present them. Autobiography is one place I know where to begin from". So, each performance unfolds in a long durational happening done over the course of one day, or several, in slow deliberated ritualised movements. While performing, Nikhil makes drawings that take on new functions and meanings, depending on the site and location. These locations are many and extend worldwide. The Yog Chitrakar Memory Drawings, the series itself, began at the Khoj workshops, and has travelled since to the cities of Oslo, Tokyo, Yokohama, Brusssels, Venice, New York City, Chicago, London, Manchester, Mumbai, Delhi, Srinagar. So, with this brief introduction, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Nikhil Chopra to speak about his work.

Thank you. It's particularly difficult to speak about performance, Evelyn, if you don't have a voice. I don't, so we'll pretend like this is a secret. That what information you are about to receive is very classified. If we can have the projector working, then we can start looking at images. Feel free to stop me in the middle of this presentation. By the way, is what I am saying audible? Can everybody understand what I am saying? Okay. I want to try and use my voice as little as possible, but I also think this is a lot of fun. If the lights can come down just a little bit, it can make the environment a little bit more spooky. And if I can have the projector going, then we can jump straight in.

I am waiting to have the projector come on because I would like to talk through images, because what I'm doing exists so much within a visual. I think I'm much more visually attuned than I am verbally attuned.

What you're looking at is not my painting, I did not paint this. This is a painting made by my grandfather. What you're looking at is a small mountain town in Kashmir called Pahalgam. I spent my childhood here. Every summer vacation, we would go and visit my grandparents who would live in this little wooden hut by the river. In 1989, of course, we lost access to Kashmir, and all that remained of Kashmir were these images or these paintings or photographs. If I were to trace back to why I like images, or where my love for making images comes from, I would say that it, perhaps, goes back to these paintings, because they are hung on my wall and the meaning of what they were, the nostalgia, the association with romance, a lost past, perhaps these were reasons why I wanted to make images, so this is the painting.

Kashmir

valley

This is the painter of that painting.

My grandfather became a very interesting entry point for me. In a sense, I was looking for clues because, at the time when I created Yog Raj Chitrakar, I was working with a fictitious character, and we'll work our way backwards, called Sir Raja, and I found Sir Raja to be very distant and, in a sense, outside of me. In order for me to create a sense or connect with this character, or connect with characterisation, I felt the need to go closer to home.

Sir Raja

This is, of course, an idyllic picture of him with his girlfriend, not my grandmother, picnicking in Germany on this lake called Lake Titisee, and what I'm struck by this image is this sense of romance that is attached to the landscape. In fact, what I'm drawn to is how the body becomes the landscape with this photograph, in a sense. Also, the imagination of the landscape and the idyllic landscape, the lakeside, the mountain, perhaps there is this deep sense of nostalgia that I attach to this image which I'm not really connected to, but I'm told about. So, perhaps my grandfather was thinking about the Himalayas in Germany in the Alps, and about the Alps in the Himalayas. So the sense of displacement and wanting to locate oneself is something that becomes very central to what I do, ...

... which is why I created the character, Yog Raj Chitrakar. Now, Chitrakar, I suppose some of you would know, means picture-maker. Yog Raj is, literally, my grandfather's name. But I also enjoy the meanings of Yog and the meanings of Raj, and the putting together of Yog Raj Chitrakar.

So, very literally, I go into the family archives and look at photographs and pick out costumes that my grandfather wore at the time, so I get myself tailored tweed coats and elaborate costuming so that , perhaps, I could imbibe this and evoke this character.

Bandra

charcoal drawings

city

displacement

family archives

history

taxi

urban

Costuming becomes very important to me because it allows me to step outside of my ordinary, allows me to step outside of my day-to-day, it allows me to step outside of my skin, and because I also use costuming as very specific signifiers, I mean I want people to read into a particular kind of history, it's not just a kurta, it's very particularly thought about.

I wanted to deal with this presentation with less of a chronological order. I thought it would be interesting to jump around time-periods. So, I'll address my 'now', which is the kind of work that is happening at this point in my life. And I'm wanting to address the city that I live in, which is Bombay.

My studio is in a very fancy upcoming suburb of Bombay called Bandra. I'm sure most of you are familiar with Bandra because it's the hip part of town. And I wanted to connect it with the other hip part of town which is Colaba, which is where all the art galleries, and the sort of cultural hub of the city is, and all the elite occupy these very protected spaces. But, in my time in Bombay, I find that connecting myself from Bandra to Colaba every day, going in a car or in a taxi, I found myself also very protected in these metallic caged objects that would wheel me from one part of the city and wheel me back, with my windows up. So, I'm very acutely aware of my position in a city like Bombay. I do exist on this side of the car window. So, as a performance, it was very important for me to relive my experience through the city, but from the other side of the window, not in any way to understand or romanticise about the lives of people who live on the other side, but just to walk through it, to walk past it, in a sense, not address it by giving myself a very specific task to do, which is to walk from Bandra to Colaba and back. On this journey, I was going to make charcoal drawings. I was going to take everything that I had to with me to survive. It was going to be 48 hours

and I started with this transformative act of shaving my head in the middle of the street, and having myself a good lunch before leaving.

So, I pack my bags, I smoke my cigarette ...

... and walk through, what you see now, is a village, a very typical Bandra village called Chimbai village, ...

Bandra

Chimbai

... past the very Catholic Bandra that we all know and love and find endearing, ...

... through the slums,

and under the big mega flyovers.

The performance also became an interesting way for me, as I've been talking about and as even Suman brought up, one of the important aspects of the performance is to locate oneself, so it becomes a way of making a map. So, just as much as I feel like a painter, I also feel a bit like a cartographer.

My costuming, as you can see, for this performance is very very subdued.

It's not flamboyant, I'm not a queen. I'm not dressed up ...

... because I'm trying to attract as little attention as possible, which is the opposite of, perhaps, what a lot of performance wants to do. A lot of performance wants to garner a lot of attention; a lot of performance wants to tell its audience, stop, look at me, whereas, in Bombay, that's a very very delicate place because you don't know when something can turn into a mob of people surrounding you.

And I will show you a performance with a mob of people surrounding me, but the context of that is very different. I think the context of it in Bombay would have been that the performance would have come to a stop.

So, I didn't want that to happen. I wanted to actually go through that experience ...

... which is why this costume is quite subdued.

So, I walk into the night.

One of the things which is a lesson that I will share with you is never ever go on a 32-km walk with brand new shoes. Ever.

Because I was beaten up, not by the tiredness of the walk, but I had blisters the size of chapatis on my feet.

So, tired and exhausted on the first day, I reach Bombay Central Station from Bandra which is already about 12 km. So, I said to myself, I've spent so much time in railway stations as a lot of art students have, making drawings and sketches of people sleeping, and this is how we learnt how to draw. So, the railway station, in a sense for me, was very much a kind of safe haven and, because I was posing as a sort of traveller, as a passerby, I thought it would be fair enough to be a traveller in a train station with my bag, sleeping on the platform. But that was not to be because the police stopped, evacuated us and, after the terrorist attacks in Bombay, it has become illegal for anybody to occupy the train platform after a certain hour.

This performance was important for me on many levels because it cleared up so much of my misunderstanding and preconceived ideas about my city.

For example, one of the things that I became acutely aware of was public space, that what I thought was public space was actually not. What I thought was free space that we all occupied, especially in a city like Bombay which is where such a large part of the city lives on the street, I thought that I would assimilate and be very much a part of that, but I realised that every single square foot of the city belongs to somebody. I cannot just go and sit anywhere. I cannot go and lie anywhere. I was constantly having to negotiate with people to spread my really large piece of canvas on their property. To make this drawing and claim that I was doing a harmless act.

Because these performances are long, it's important that I'm constantly listening to my body as well. The idea of eating, drinking lots of water, eating things like fruits and rehydrating myself, resting, these things become built in to the work. So, in a sense, these little, not little but vital, acts of nourishing the body also become spectacular or go on display, if you want to think about it that way.

So, Chowpatty Beach. This is happening in January, but January in Bombay is not like January in Bangalore. Also, it's hot, very hot. The hunt, also, of this character is not just to go into any location, but there is this dying need to find, I'm dying to look for open spaces. I'm constantly on the search for that in Bombay, and I realised that our open spaces from our cities are disappearing so fast. I think that most of you who live in Bangalore are very aware of how this builder-politician nexus is kind of squeezing us. So, these are some of the last few grand open spaces left in Bombay. Of course, now we're in the middle of Oval Maidan which is almost at the southern tip of Bombay.

Chowpatty

Oval Maidan

I finish my day's drawing over there, and...

... walk into the night.

It's also important for me to pick on certain iconic, historically used, historically seen images that take people to a place in the city which is iconic. I suppose, because it's important for me to be very quick and clear with locating, so when I lay down something like the University Tower, it becomes very quick for people to say, Ah! this is Bombay. And I want that point of entry for an audience, I want them to find this familial history, perhaps relationship, to make with their own experience with the city. So, it's not just a random neighbourhood, but it is the neighbourhood.

This is on the third day, which is the day that I'm walking back.

I go back.

I finish the drawing. I have a half-time photograph for you.

A blister photograph. And I start to walk back.

Dadar

Bandra

And back where I started.

Now, the other preconceived notion of Bombay that was taken away from me was one that Bandra, in fact, is the most liberal neighbourhood, perhaps in the most liberal city in South Asia, would you say? I would say Bombay is probably the most liberal city in this country. In fact, I ran into a lot of problems with the neighbourhood that I started my performance in, because they had a problem with the fact that the performance was not entertaining, and that the performance was actually embarrassing, because it involved a semi half-naked man and cutting hair. So, that kind of catharsis and that kind of act that one associates with, perhaps, death or sacrifice did not go down okay. So, that preconceived notion, as well, was broken.

Please feel free to stop me at any point and ask any questions. Shall I move on to the next project?

Memory Drawing 2. What I showed you last was Memory Drawing 10. In a sense that this was a project that really kind of set off what it meant to be in a performance for a long period of time. So, this was the first performance that I was doing that was of that length. It was 72 hours long.

Bombay audience

Colaba

memory drawing

viewing art

It was in a space in Colaba. The space had a camera on the roof of the building. I had a switch for that camera. That camera could rotate 360 degrees.

And what that camera did for me was, on the wall that you can see behind, projected the image of what it was catching. So, it was sort of a surveillance camera. Now, that video became a reference window for me and I could, in fact, look at the entire city 360 degrees around me. The idea was to replicate or to recreate the city around me in the form of a drawing, in the form of an illusion. So, let's say for example, if this was the wall, the camera would be catching the building that would actually be behind this wall. So, in fact, the idea, or the struggle of this trapped character in the box became the drawing, in a sense, to make the walls disappear.

But, of course, there is this elaborate ritual that comes around eating and feasting and setting up still-lives that resemble paintings.

Then, of course, sitting down after dinner and looking at the sea-view, as a lot of people would, perhaps, living in Colaba.

The sleeping, of course.

To me, this performance was important because it also challenged a certain Bombay audience to break its norms about how and what viewing art is, because it brought people to look at an artwork, not just once, but people came back a couple of times, if not three-four times. It also allowed the audience to come at any time, day or night. In fact, it would be interesting to see a bunch of drunk friends land up after the bar at 3 a.m., screaming and saying, Hey, we were here, and then suddenly realising that somebody is sleeping, and then sticking around. Some people would bring their guitar, and there was a little balcony outside, so it sort of became a performance for an audience to be participative, or as an extraordinary audience, as an audience that says, Oh! I'm going to see a performance at 3 a.m.

That, to me, was quite telling about the idea of duration and the aspect of duration.

One of the things, of course, in the performances I do, is I take a vow of silence. I don't talk to anyone, I don't exchange any words, I barely make any eye contact with anyone. I'm immersed in my own tasks of making drawings, essentially.

This is about more than three-fourth of the drawing complete. Where these buildings stand is where they, perhaps, would be if there were no wall.

The thing about durational work that excites me most is its transformative power. Spending that kind of time in a space.. Of course, there are a lot of artists who have worked with duration, but what this kind of time duration does is it really... Of course, the space is transforming, but there is a physical and an internal transformation that happens, and then there is this need to express that transformation, because it just can't be the walls, it also has to be the body. So, the transformation and the charcoal on the walls bounce off from the walls and on to the body as well, which is why I go through this ritual of shaving and cutting my hair.

And, of course, there is this elaborate ritual of washing and taking off the charcoal. And, as that charcoal comes off, and as that face gets shaved,...

... the question is where does it stop, and you go on, and I go on, because I start with wearing make-up, and I start to...

... put on a crenoline,...

... and I crawl into a dress, and...

... and crown myself the queen of the moment.

At the end of the performance, I, of course, close the window that I have been using for the three days,...

... and pose.

Q1. Why the queen?

A. A lot of the research to these performances come from the location and, to me, I was quite interested, not just in my own relationship, I suppose, with a very colonial, Victorian past, but also the fact that how much of this part of Bombay is colonial and historic. I think by becoming the queen, I felt that I was reclaiming some of these histories. Because I had dealt with the idea of the king, I thought it would be quite obvious, in a sense for me, to have crowned myself a king, but I think by engendering myself and regendering myself, I felt a certain sense of empowerment that I think performance attempts to do. That empowerment is not just mine, but I think is passed over. I think a really important aspect of it is that a sense of saying this is mine also is transmitted to an audience. At the end of that queen's walk is the first time then I actually make eye contact with everybody in the room.

Q2. Why do you keep shaving the head?

A. I think I associate a lot of things with shaving of my head. Firstly, there is so much of vanity, I think, that we associate with our hair, combing hair and addressing hair. Now, I'm losing hair. I also think that in our culture, when someone passes away, when someone dies, you shave your head because it's a way of saying, I'm done with the past and into the new. So, the act of shaving really kind of allows me to make a shift in, let's say, a performance. Suddenly I've gone from this very masculine, macho, bearded character, hopefully, to this coal-miner looking, beaten-up, shaved, exhausted fakir, almost. It helps me to create this juxtapositioning, or this kind of range, in a sense, of what happens to the body when you see it without hair. In fact, this project deals a lot with hair, as well.

Q.3 Who took the photographs?

I work quite consistently with a photographer, and she's been quite consistently documenting my performances. So, yes, the documentation aspect is something that I'm really rethinking about it. I'd like to talk about it at some point. After the presentation, I'd like to talk about it, maybe, where documentation or performance is headed to me, because I feel I have too many pictures, I have too many photographs.

So, let's move on to this project.

This is a festival in Brussels that happens every year. It's a theatre festival. It was an interesting opportunity for me also to step outside of the visual art world, because of my training has been so much around the visual arts. Theatre has been an important aspect, but it was interesting that it was being read in the context of theatre.

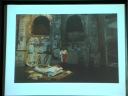

The Brigittines is a chapel where I am performing this. It's a baroque chapel. It's been used as a theatre for the past 50 years, so it has all this great infrastructure of theatre, great lights and a kind of fantastic space, a total fantasy space for a performer.

The idea was to occupy this space, but this was going to be a 96-hour performance. Now, all the food, drink, water, everything is always on set, and very little gets brought from outside. It's like when you go on a journey, what you take with you, and this is what I think about when I'm doing a performance work.

So, this is the next morning,...

... I get dressed up and...

... take a drumset out, but walk to...

... the top of the city from where you get this panorama of the city. It's also called the Palais de Justice or the Supreme Court. As you can see,...

... it's an obnoxiously gigantic neo-classical building.

It also struck me that there is this building that sits on top of a hill, almost judging a city. And Brussels also struck me very much as this kind of neo-classical city, very much like 18th-19th century, which rung very well with the Chitrakar character that I suppose, at least for me, it worked really very well with this character that I had created.

I go back to the same spot in the city twice, and I dealt with the panorama of the city on two large pieces of canvas, one from left to right, and one from right to left.

And what, essentially, I would do every evening would be I would come and I would display the drawings that I had made of the day. So, even when I would leave the next day, the drawings I had done of the previous day would actually be left in the space. So, even when I was away, the audience that would come to the space would get a sense of this idea of a space that was transforming, even without seeing the performer in the space.

The shaving...

Now, I also wanted to see what the potential of drawing is. Is drawing something that is always representational in that sense where it's becoming this landscape backdrop for a portrait, or is drawing really truly a means of documentation? Because I'm really, at this point, thinking about how the whole process of performing in itself was a process of making documents. So, it's not just making sceneries and vistas, but I also start to make rubbings on the blank canvas of the walls and the brickwork.

On the fourth day, I go to the flea market,...

... the market where second-hand goods and used things,...

... and old paintings, and old stories, and crockery, cutlery, things from people's home, every object over there has a history. So, I found it interesting to be wedging my own history, or displaying my own stuff in this flea market.

So, I make this drawing.

This is the last day which, out of no fault of people, has been called the Gandhi Day. I didn't expect that to happen, but it's funny how you kind of fall into that trap, actually, when you think about identity. As much as possible, I did not want to look like...

... Gandhi, but as soon as I saw my silhouette and my shadow, and those round specs, and my hunch and the shawl, I was like, Oh my God!, where's a cigarette.

I think you can't help these things, and then I asked myself, Why is it, why is it that this is happening?

It's probably because of all of this that one is going through, that it's not just being read like that, but it's also being played out like that. I am thinking about, in a sense, of how Gandhian in a way my practice is. Well, it's about walking into public spaces many times without permission, and doing a completely non-violent act, but with being completely non-cooperative, in a sense, with certain authorities that want to stop you and say, No, I don't want to stop, I'm going to continue, and the policeman is talking at you, and you are pretending not to listen.

Gandhian acts

architecture

neo-classical

panorama

resistance

So, I find that kind of resistance, for me, I also really enjoy and relate to that.

So, of course, the panorama of the city is now stitched back together again, but because the measurements of it were not correct, it's sort of fractured. To me, the associations that came out of it, the conversations that came out of that broken fracturedness, because of this familiar cityscape which everybody in Brussels recognises like that, it brings up other associations which is like, for example, somebody said, You know, where that crack is, where that stitchmark is, is exactly the place that I fell from when I was seven years old, and I'm like, Oh, okay, that's interesting. The other thing that people really bring up is that how this may address how culturally divided Brussels is. There is this deep divide between, let's say, the Flemish-speaking and the French-speaking. So, even though these are things that I'm aware of, I'm not trying to force these things, but these are associations that are being made already, so I'm kind of walking into these associations.

And, of course, as the drawings go up, or as the painted backdrops go up, the portrait is being made ready,

which is the end of the performance, and now I'm really addressing shaving.

So, the shaving doesn't stop at the face anymore.

And, as you can see, the rubbings actually reveal. Because the dealing with architecture, and especially dealing with beautiful architecture, you're always conflicted on how you would work with it. The idea was not to use the canvasses to cover the building, but use the canvasses to reveal the building as well. So, these rubbings, in a way, became the way in which to reveal the arches, and they were just charcoal rubbed into the brickwork.

And the final portrait against the painted backdrop. You may wonder why there is this obvious Greco-Roman reference that comes straight out of my reaction of being in a place like Brussels, which is such a Greek neo-classical obsessed city. The idea was to become the marblesque sculpture in the middle of that square.

Are there any questions before I jump into the next project?

Okay, so this is a project that was very unusual for me. It was a performance exhibition. I was performing with eight other performers in Manchester, and this was part of the Manchester International Festival. It was curated by Marina Abramovic who is one of the grandmothers of performance art, and Hans Ulrich, the Director of the Whitworth Gallery. We were all given a space, perhaps as big as this. I had a space actually probably double the size of this room, so I was like, What am I going to do with it? The other thing that was new for me was that this was going to be an 18-day long event, whch meant that for four hours every day, the audience would come, and when they came from that, I can't remember, but I think it was about 4 to 8 p.m. every day, so from 4 to 8 p.m., if you came at 4, you first went through a certain initiation process with the great Marina Abramovic, and you were all given lab-coats as an audience, and your watches, your cellphones, your any association with time and place were taken away from you. So, the audience here was being subjected, and was being asked to play a very very specific role, as an audience always is, but here, I think, the audience is being made very aware of that. It was interesting for me as a performer because the audience then truly became one body. It was difficult for me to recognise, Oh, there's my friend, Oh, there's Durga, or there's Evelyn, because it put everybody into one space, which actually is less distracting, and actually forces you to focus. Now, I have very little documentation from this performance, in terms of documenting the entire 18 days. And I think it's because probably somewhere a lot of people who are working with performances that looked. So, every day they came back to their space and did the same thing again, whereas for me it felt like I needed to go through those 18 days and not on a single day the performance had to be the same. So, every day the performance changed completely because I was dealing with blackening, taking a white space and making it black with charcoal. So, what you see on the back wall is actually charcoal drawing.

Hans Ulrich

Manchester International Festival

Marina Abramovic

illusory landscape

So, these are images. This are probably from the 10th or the 11th day.

Now, what I did also was that, when I had blackened this space, it was an opportunity also to create this illusion of a landscape for me. So, I had taken this painting made by my grandfather of Kashmir, which was about this big, and I replicated that painting on that wall by erasure, by erasing.

So, on the back you can see that it's just mark-making. Now, towards the end of the performance I erased that landscape as well. So, the landscape appears in the course of the 18 days, and the landscape disappears as well. So, you can see traces of it on the back wall. No, you can't actually, I can.

Bringing the queen back to Manchester has its own implications.

And, of course, at the end of the 18th day, I leave the space. So, the idea of entering the space and exiting the space was also actually very important.

I'll jump back to 2005. This is the Sir Raja III project that I was doing in Bombay. It started in America, but when I came back to India, I felt the need to test out, or play out, some of these ideas that I had touched upon when I was doing my Masters. I was also going back to Kashmir after many years, to Pahalgam, at least, after 1989, this idyllic place that I've talked about. I, in fact, went back into my grandfather's paintings; I wanted to trace back and go, perhaps, searching for those locations based on the paintings, or perhaps where he may have sat and painted them and, in a sense, wanted to insert myself in them, so that I was actually really wanting to relive that time and place. And all of his paintings are actually made on location. He would go out with a little pad and watercolour set. But there was a performance I did that went with Sir Raja III, the photographs, and that was of me lying there in this very chiaroscuro lit, very Caravaggio-Rembrandt-esque, baroque-esque lit set, and I lay there motionless, as if I were posing for a painting around my own death.

Pahalgam

Sir Raja

And, finally, this was the work that I graduated with, which was Sir Raja II.

Now, while I was in college, I was doing a lot of research around early Indian photography. Especially, I was looking at photographs of Indian dignitaries from the turn of the previous century, and before that. And what struck me a lot was the irony in these photographs because these maharajas, as they posed with all their pomp and regalia, they posed as leaders, but on their photographs signed their allegiance to the Crown. This position of being ruler and subject at the same time, and being sandwiched in between these roles, of a dying tradition almost, seemed really interesting as a subject-matter at the time.

Crown loyalties

Indian rajas

early Indian photography

exoticism

Especially, because while I was in college I was being asked this whole question about, no, not asked this question, I would fall into the trap of being exoticised, or the more neutral I tried to get with my subject-matter, the more I would be exoticised. So, I said that, Okay, let's really take this whole idea of exoticism and flip it on its back. Let's create a situation, for myself also, that is so out there and exotic that then we are all experiencing the same thing,...

... then we can ask this question of what we mean by exoticism. So, I created this Dutch still-life dining-table set and, of course, I was reacting to this country of excess, and supermarket culture and Thanksgiving meals and, when you order a hamburger, it's actually for four people. So, I was reacting to that and, of course, everything in this Dutch still-life is from the giant supermarket that was close to my house, so, lobsters and crabs, etc., all the food was warm, you could smell it. The performance was a one-time performance, it lasted two hours and, while it was happening, the food was slowly slowly smelling, specially because it was May and it was warm, and the sea-food was getting contaminated. But I sat there on that table, motionless, refusing to pick up a single bite and eat. All that the audience was served was water, and it was quite intentionally at dinnertime, so the audience was hungry when they came.

What becomes really clear to me, actually, with performance work, now that I feel like I have gone through a few performances, is that the desire in an audience to see a performance through is so much of what completes the cycle between performer and audience. Whenever a performance for me reaches a crisis point, like at the railway station, for example, in Bombay, it became extremely clear to me that the only people that saved me actually out of that situation, that blister-ridden situation, was the audience, because they wanted to see me through, as much they wanted to see themselves through, this experience.

I'll leave you with one last piece, it's a video.

Q1. As a woman and as a feminist who, perhaps, thinks about performances as assertive, natural (?) acts, or as an act that, sometimes, you are mired into and enveloped by. Do you, as a performance artist, feel that the depth and potential of your work is diminished by the fact that it is so located in performance?

A. I'm hoping that, because it is immersed in performance, in fact, it is amplified as opposed to diminished, because you bear witness not to an act that you imagine but to something that you actually viscerally experience by being there, and because by experiencing it as it is happening. I think that maybe they're projected out more, or they are louder than they would be if these were Cindy Sherman-esque, sort of studio explorations, or private kind of acts that happened in a studio space in solitary. I think the fact that because they are live and because they're carried out in plain view, I think that, maybe, these are... I'm repeating myself. Does that answer your question?

embodied performance

immersive performance

Q2. Is this connected with what you said about the audience wanting to be part of the the whole process? I saw your work at the Venice Biennale, but you were not there. That was a very interesting experience. How much do you allow your work to be seen without you being there as well?

A. That's a really great question, and I think that goes back to the whole documentation question that we were talking about. Now that I have just immersed myself so much in the idea of being photographed to death in performances, I'm now thinking about how to expand on the idea of documentation of a performance, because what you see as a piece after a performance, I think what you are looking at is remnants of a performance, or you're looking at documentation of a performance, and you're not looking at the performance. So, even though, let's say, residue from a performance remains in a space for, let's say, an extended period of time, it's still the residue of that work. It's not the work. It is the work, but I think it's another work. It becomes another piece. It becomes, maybe, an installation, or it becomes a sculpture, more than it does a live performance.

documentation

residual performance

Q3. To me, it seemed like such an intense experience for you, and totally without words, that the whole process for you is very important. Probably, it's only after the documentation that, when you see it, you see the other dimensions, isn't it?

A. Absolutely, absolutely. It's only in retrospect .. I think there are two things that are happening. I think when you are immersed in the performance, when you are performing, of course your brain is working at 100 kms an hour, whether your mouth is or not. In fact, there is a whole set of questions that come up during a performance, then when you get out of a performance, when you come in contact with all the documentation of a performance, and that's not just photographs. I think that performances get documented in memories of people as well. So, when you hear the narration of your performance back at you, or when you look at pictures, or when you look at the installation, or you come back after two days or three days and look at the drawings on the wall, I think that being in it and being outside of it are two very different experiences. And I'm hoping that with each one, a whole new set of questions, and a whole new set of ideas, unfold.

Q. I really enjoyed seeing it. It's wonderful to see exploration of this kind which has so many more dimensions.

A. Thank you, thank you.

performing memory

Q.4 I'm curious. You said your mind works at 100 kms an hour. What are these thoughts, or just randomly? What do artists think? You said you don't make eye contact with people and that you're not really looking at your audience. So, unless you are completely immersed in your work, then what is what you're doing? What is that? How do artists think?

A. I think that I'm constantly battling between telling myself that I'm in a performance, or who are the audience, or I must put on the show, to giving myself these tasks which actually take me away from that thought. So, as much as possible, I'm trying to give myself these laborious tasks to do, like making these drawings, let's say; the first one was 300 feet of drawing, the 72-hour performance. So, in a sense, I think that the act of drawing in itself is such a quiet, introspective, meditative, calculative process that, actually, the audience is something you suddenly stumble upon when you're making the drawing, do you know what I mean? It's actually a relief to have this skill that you can, or at least work at that skill. And that is an act that requires a lot of rigour, so that that can then become the script of the piece. There are other things then. So, if I'm drawing drawing drawing drawing, then I'm hungry, then I'm tired, then I'm wanting to rest and sleep, or whatever it is. But all of those things are always going back to the task that I've given myself, I have to keep telling myself that, no no no, don't worry about whether this room is empty or full, don't worry about whether it's day or night, don't worry about whether you're hungry or sleepy, you don't worry whether you're tired or energetic, you have to finish this work, which is like how any task works, I think. Like, if you have a project that you are working on, there's this brother, sister, whatever, dog, cat, that you have around you in your house that you learn how to develop mechanisms to block those away, so that you can then allow yourself to be completely immersed.

Q. With regards to emotion?

A. A whole gamut of emotions. I think it's all the emotions that you could think of on a day-to-day, which is the pressure and the stress of having to go through the performance, the fear and vulnerability of being watched while you're doing it, the joy and jubilation of a captive audience, the joy of reaching the end of the performance and the sense of relief that comes with that, the feeling of getting absolutely drunk sometimes, also, in a performance, because I'm going overboard with the eating and the drinking. So, it's a gamut of emotions, and I think that the audience is experiencing those, or at least, I'm wanting to transmit those emotions without really acting, but I think it's more like reacting than it is like acting.

emotion

Q5. I saw your performance in the Venice Biennale, and it was a 48-hour performance, and I actually did two different times in one day, so two days in your program. So, I saw it from the beginning, it sort of progressed, and then I also saw it after you were done with it. The tower was just left like that. This question was in my head since the time I actually saw you perform. At that particular Biennale, did you choose that particular place or were you given that particular place?

A. I don't think, at the Venice Bienalle, we can choose any space. But that specific space was given to me, and that was the only space. I think I was the last entry into the Venice Bienalle, so it was like fully backdoor entry because of the tower, because the curator who had seen the performance at the Serpentine Gallery, which you were there for, Suman, wrote back to me saying that, Would you like to be part of the Bienalle because I have a space that I think would be interesting for you to be in, and I didn't look at the space and I said, Yes. But it worked out, I think it was a very clever choice by the curator, and I think it worked quite well for what I do, so I was very happy to have that sort of space to work with.

Q. All the other spaces were extremely large.

A. Yes. For people who weren't there, it was an Austro-Hungarian 18th-19th century tower, a watch-tower that sat at the edge of the canal and the sea, and it became very strategic in terms of being what a watch-tower does. So, I actually remade it into a watch-tower because I planted cameras on top of the watch-tower, and used the cameras to make drawings inside the watch-tower. So, I was actually watching from the watch-tower, so it was quite ...

Q. Another work which was the one you did in (?) Part 3, 'Make the Walls Disappear', by drawing on the walls. I could relate that a little bit to this.

A. Exactly. I think, for the Venice Bienalle, I was going back very much to the performance I did in Bombay, and taking ideas from it and using it, specially also because of just the nature of that building and that circular kind of tower just made sense that 360 degrees would be something I would address again.

Q6. You're more of a performer, and the act of drawing is more of a tool for you in the performance. Why is it your Sir Raja Chitrakar not a performer because you tend to paint on your grandfather's things (?) You tend to go back to that painting of your grandfather (?) Could you talk about that a bit? (?)

A. If we have to go back, I could probably even go back to the first slide about this whole idea of where this need to make pictures comes from. It's this need, in a sense, to not just document but to capture memory, and to make memory stand still, or to embalm memory forever. I am a painter, my training has been that of a painter. I went to art school and studied. The beginning of my art education was canvas painting and, of course, I later on went and diversified into other things, but even my Masters is an M.FA in painting. So, I'm attempting to be aware of my own approach to artmaking and, especially because it's visual artmaking, I think the Chitrakar or the picture-maker is something I relate to more than the idea of the performer, because the act of making pictures in itself is performative, whether you are in your studio alone or on the street doing this as an act for public view. You see the performative in something like Jackson Pollock's work. This is an intrinsic part of his work, the idea of the body moving across the canvas. So, I do think of myself as a painter before I think of myself as an actor, and I do think of myself as a picture-maker before I think of myself as a theatre person, or even as a performer. Because even my performances are wanting to refer, in so many ways, to painting, especially also because the performances go back into painting, go back into the two-dimensional framed photograph, or the two-dimensional picture that are are seeing up here. So, the references to painting and picture-making are the constant, even without the drawing. I find that the Raja pictures are as much about picture-making and chitrakari as the performances with the drawings are.

Bangalore, India

Q7. To me, there seems to be a sort of a disconnect between the two types of spaces that you work in. One is the natural space which is Bombay and the last video that you showed us with real people, and the other space which is sort of contrived, of the Chapel, whatever. In one of them, that is the contrived space, if I may call it that, people seem to take back memories, somebody talks about being in Venice. My question is, does it bother you that, when you actually get into the public domain, the real public domain, that people might just think of you as mad, and just go about their business, and actually not really be affected by your performance at all. Therefore, I want to know the purpose and meaning. For example, the gallery, but that's rarefied, that's very, like you said, upper class(?). What happens in the real time in the real world?

A. That's a great question. Most of the times, in public spaces, I go unnoticed also because I'm a freak on the street, like many freaks on the streets, specially in big cities like Bombay. But I think that what I relate to with performance, first, is the fact that the act of performing is first for the self, that it's first for me and my exploration as an artist, about what the nature of my practice is, and then it's something that the audience experiences. Here, I'm makiing very close distinctions, very close relationships between, let's say something like a walk through the city and a pilgrimage, for example. When I got into trouble, let's say, in Bandra for cutting my hair and being in an underwear, my argument to them was, perhaps, that this was like a pilgrimage that I went on. So, the idea of enduring that experience is something that gets transmitted, not just in, let's say, my body but it also gets recorded on the canvas because I'm coming back with a record. Like, let's say, for example, in the Bombay performance, I'm coming back with the drawing and, hopefully, what that drawing contains is, not so specifically and overtly, but it does contain some of that tension that was experienced while making that drawing in the public space. Like, for example, the Kashmir drawing doesn't look anything like what is out there, it's just a bunch of scratches with black and white on the street. But that's purely because of the fact that public space is so raw and you are actually at the mercy of the public, and how do you negotiate yourself through. That I find much more challenging, actually, than I do for being in a protected safe clinical gallery space.

Q. Then why were your drawings in Bombay and Brussels so literal, as against the one in Kashmir that actually was quite..

A. That's because of the set of circumstances that all those three public spaces come with. I mean, Bombay seemed so much calmer than Srinagar. There is underlying tension, of course, but it's not this direct representation of that tension. I think it happens, it's not something that is going out there and planning it, or saying, Oh, I'm feeling the tension, so how do I create that tension in the work. That's not something I'm thinking about at that point at all. I'm saying, let's finish this damn drawing and get the hell out of here. I think it's from that place more than it is about being literal.

Q. You're saying to me, Just shut up and let's get out of here.

A. Not at all, not at all.

freaks on streets

spaces of performance

Q8. Because each performance is such an intense experience, how long does it take to recover from that?

A. Five minutes and a glass of wine. Really, it takes no time at all, like, Ah! it's done.

Thank you very much, it's been a pleasure.

Pad.ma requires JavaScript.