Photojournalism - Interview with Mukesh Parpiani

Director: Nisha Vasudevan

Duration: 00:48:43; Aspect Ratio: 1.778:1; Hue: 101.869; Saturation: 0.009; Lightness: 0.359; Volume: 0.283; Cuts per Minute: 0.493; Words per Minute: 116.008

Summary: Mukesh Parpiani is currently the Head - Piramal Art Gallery, NCPA. He has previously worked with The Daily, Indian Express and Mid-Day. Mukesh has made photographs during the Gujarat riots, and during the Bombay riots. He's made photos of Indira Gandhi and of the Mumbai police. Having been in the field for so many years, this veteran photojournalist also helps us understand more about how digital media has changed the field of photojournalism, about sourcing and editing, and how one goes about on his/her beat. This interview with him spans over his whole career and has him giving us insight into his most iconic images, and those that have been closest to his heart. It also focuses on the questions of the ethics of photojournalism - to shoot or not to shoot when the dilemma is that of the dignity of one life vs. the disperal of information? Mukesh also tells us what he thinks about censorship, the subject's consent and invasion of privacy. This is especially brought out through the photographs he has taken of Aruna Shanbag. Through gripping anecdotes, Mukesh has brought out some very interesting and essential points when it comes to the ethical dilemmas faced by photojournalists.

Interviewer: Reema Sengupta.

filters

censorship

consent

digital photography

ethics

privacy

Piramal Gallery, Mumbai

Reema: Alright, so, how is it that you actually ended up becoming a photojournalist?

Mukesh: See, my brother used to be a hobby photographer, and before he left for the U.S. in the '70s, post-'70s, he left his camera with me; he had a dark room and all that at home. So you can say that photography was in my blood. And subsequently I took up the courses in the various photography fields - like portraiture, composition, dark room, photojournalism. Then I learnt under the Professor Pillai who used to teach at Indo-American Society at V.T. I did several courses with him, very long stint with him, and then i moved on to Xavier's Instite of Mass Communication.

This interview gives candid insight into the practice of hard news photojournalism in India.

Here is an excerpt from the article 'Visual Sociology, Documentary Photography, and Photojournalism: It's (Almost) All a Matter of Context' by Howard S. Becker (Visual Sociology, 10 (1-2), pp. 5-14 © International Visual Sociology Association, 1995; accessed from

http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/863122__794687495.pdf on 08.09.2010). It addresses preconceived notions about photojournalism, stereotypes of photojournalists and what contemporary photojournalism has evolved to become:

Photojournalism is what journalists do, producing images as part of the work of getting out daily newspapers and weekly news magazines(probably mostly daily newspapers now, since the death in the early nineteen-seventies of Life and Look). What is photojournalism commonly supposed to be? Unbiased. Factual. Complete. Attention-getting, storytelling, courageous. Our image of the photojournalism insofar as it is based on historical figures, consists of one part Weegee, sleeping in his car, typing his stories on the typewriter stored in its trunk, smoking cigars, chasing car wrecks and fires, and photographing criminals for a New York tabloid; he said of his work "Murders and fires, my two best sellers, my bread and butter." A second part is Robert Capa, rushing into the midst of a war, a battle, to get a close-up shot of death and destruction (his watchword

was "If your pictures aren't good enough, you aren't close enough" (quoted in Capa 1968) for the news magazines. The final part of the stereotype is Margaret Bourke-White in aviator's gear, camera in one hand, helmet in the other, an airplane wing and propeller behind her, flying around the world producing classic photo-essays in the Life style. Contemporary versions of the stereotype appear in Hollywood films: Nick Nolte, standing on the hood of a tank as it lumbers into battle through enemy fire, making images of war as he risks his life, The reality is less heroic. Photojournalism is whatever it can be, given the nature of the journalism business. As that business changed, as the age of Life and Look faded, as the nature of the daily newspaper changed in the face of competition from radio and television, the photographs journalists made changed too.

Mukesh: I did Mass Communication there for two years, and then I stared shooting in the streets of Mumbai. That was I think around '78-'79 and I did three years of freelancing for the various newspapers as well as the magazines. And then, a tabloid was being launched in Bombay in those days, called Daily. I joined them as a Chief Photographer in 1981. We were two of us, myself and I had a one Parsi colleague of mine. We both worked for that newspaper day and night and made it a big success. That, unfortunately, the paper goes down after a ten year stint. And from there I moved onto the Indian Express who had a team of 12 photographers there, as a Photo Editor, and we had a one-after-one-after scoops.

Mukesh: In the Daily we were the only two people covering the long Mumbai city - from Thane, Borivali to Fountain whenever something happened. And in the Express I got a team of dozen people and then me, I was told to cater to seven newspapers in Bombay. They had English, Hindi, Gujurati, Marathi newspapers plus couple of magazines and a Financial Express. Plus 17 editions - so they really gave me very good team at the Indian Express, and I diversified into...more in the co-ordinating, and getting the news...photo-news coverage done for the entire group of Indian Express. Rather shooting more, but I did not stop shooting there, I had many strong pictures during that period including '92-'93 blasts, riots, Ahmedabad riots. And so I established my team as the one of the...you can say...not best in India, but at least in the western part of India if anything happened, we were on the spot in the shortest period of time.

Mukesh: We developed the Pune, Ahmedabad, Baroda photographers also into our network. The moment anything happened, quickly we rushed and covered it, and put it on the wire photos - those days no email. So we had to process in a black and white dark room, put it on a laser roller scanner. It used to take 12 minutes to transmit an 8x10 B&W photograph by a trunk telephone line.

Today's photojoumalists are literate, college educated, can write, and so are no longer simply illustrators of stories reporters tell. They have a coherent ideology, based on the concept of the story-telling image. Nevertheless, contemporary photojournalism is, like its earlier versions, constrained by available space and by the prejudices, blind spots, and reconceived story lines of their editorial superiors (Ericson, Baranek, and Chan 1987).

Mukesh: Now, things have changed. Looking at the success at the Express as the finest photo team, we had at least 3 exhibitions of my team including one in the gallery downstairs.

Reema: That's Piramal Gallery.

Mukesh: Yes, Piramal Gallery, this is the 22 year old institution dedicated to only photography as an art form.

Mukesh: From Express I moved on to Mid-Day, and in Mid-Day we changed the entire team into digital. We shut down the dark room, switched over from the film to digital. I equipped even the reporters with a small Coolpix camera -that, "whenever you come across something in the streets, please do shoot. Besides that you can even shoot your portraits or the story pictures where you need not waste the time of the photographers." That much freedom I got from the management of the Mid-Day.

Mukesh: I stayed on there for nine years, again, we had a very good continuation of the good work we did in the Indian Express. And we won seven awards in span of four years for my team, including free Nikon cameras from the Better Photography and so on. So, under the my umbrella at least 50 photographers have come up in the span of last 20 years.

Mukesh: And, from Mid-Day I have moved on to this place to sideline myself from hard news, to little more creative and the artwork - I had my three shows in this gallery. And then I got this challenge here to build up this gallery equally powerfully well in the competition of so many galleries coming up in the city. Once, there were only five, now there are 20 galleries in Bombay, catering to the art as well as photography. So this is another challenge I am facing since last one year and hope to do something well, we have a good two shows coming up. One is now, is by NIP, National Institue of Photography from 17th August, and subsequently we have another show coming from the wildlife photographers in the end of the August.

Reema: Right. You mentioned your stint with Indian Express, you all were very prompt. Could you tell us about your chain of information, where you got your information from, and how that worked out - was it from the police, did you have informers, how did that work?

Mukesh: See, today we have so many channels. In the Daily newspaper we had no newspaper except Doordarshan and a couple of local channels. We had no pagers, we had no mobiles, whatever the network was to call up fire brigade, call up police, constantly every two-three hours and keep finding out what's happening in the city.

1. The Indian Express is a newspaper which is known to be anti-establishment. It's coverage of the Bofors Scam (along with the Hindu) among others, has become a landmark in the history of the press in India.

2. This section of the interview gives a lot of insight into how the chain of information for photographers worked in an age without mobile phones, pagers, social networking, even transport, and without the constant stream of information that the internet provides

Mukesh: But the way the technology changed, way the media grew, in '90s several new newspapers came up - throwing up the big competition for us, as well as the lot of job opportunities too. The source of information is...in those days was mainly police and fire brigade. But in '90s it changed to the pagers, we used to leave our card wherever, whether we went on a police station or we went to the hospital or wherever we went and we built up a rapport with the person who's little P.R.-oriented or the people who's interested in informing media including the political and social workers. They used to call up the office and we used to get a message on the pagers. That was the networking in those days and subsequently once the mobiles are in there is no dearth of the news coming in.

Mukesh: I remember the...just 3 years back, a new bus was being launched from Andheri railway station, it's a, you know...new BEST bus, imported bus, they bought it at the cost of I think over 50-60 lakh rupees. My men covered the inaugaration at the Andheri station and we took a train from the Andheri to come to the office. At Bandra, it caught fire. We had to get the pictures...bus in the flames.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: That man had not even crossed Mahim station when we got the news. We told him, "Get down, go back to Bandra, the bus has caught fire." But the fire was extinguished by the time he went there and he shot the pictures. Then I told him, that look around whether anybody has shot the pictures. Luckily he went for a cigarette and the cigarette-wallah told him, "Yeh dekho, mobile mein humne photo nikala." ("Look at this, I have taken a photo on my mobile.") Because he was carrying the camera, so the panwalla said yes. We took pictures from him, the live pictures of bus in the flames. This is just off the hand, one example I've given you.

Mukesh: When we go to the spots we don't only look for our own pictures. We also look around if somebody has a better picture or something still better. Like, we rushed to the riots in Baroda. By the time we landed up in Baroda the Baroda guys have shot. So the responsibility of my guy flewing [sic] in from Bombay was to get some images from them and mail it to us before he starts his own shooting there. This is the strategy we have developed.

Mukesh: And the other networking which I started at Indian Express was that, in those days even mobile was not there and we were very dependent on the landlines. I choosed [sic] if each photographer in my team from different suburbs of the Bombay...if somebody is in South Bombay, if something happens at the South Bombay he will be quickly informed. If something happens in the Borivali he will be alerted. If something happens around say, Sion-Kurla, he will be alerted; and everybody with two-wheelers.

Reema: Okay.

Mukesh: Anyone who wants to join my team, the my condition was, "You must have a two-wheeler."

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: Today everybody has a two-wheeler, mobile, lap-top, digital camera. Even a local freelancer today does that. So this is the style I have started which is in vogue even today.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: You know, so this is how we landed up on the news spots and we got the better pictures than our rival newspapers.

Reema: Right, also, tell us about the most heart-rending picture you've taken in your journalistic career.

Mukesh: See we enjoyed shooting Mrs. Gandhi.

Reema: Okay...what was the situation, where was it, when did it happen?

Mukesh: No no no, it has been...see, in the current trend you are 500 feet away from a celebrity. In those days, we could travel in the convoy of Mrs. Gandhi.

Reema: Ah, okay...

Mukesh: Today we can't...

Reema: Right. Definitely.

Mukesh: So you have a proximity, shooting at this distance to her.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: And when you spend the whole day her Bombay visit, you get dearth of pictures. And that lady has a charisma - landing up at 6 in the morning at flight from Delhi, addressing the press conference at 7:30-8:00 in the evening, non-stop travelling in the city at various venues. So, it was fun shooting her, I have a great collection of her.

Mukesh: And there are a lot of events like...I shot lot of pictures of J.R.D. Tata. The biggest plus point is that, wherever we are, I have been in a very formal habit...for whoever has worked under me that, "Even if you are going out to drop your child to a school, you must carry a camera with you."

Reema: Right, so it's all about spontaneity.

Mukesh: Spontaniety. You can't get same frame again.

Reema: Definitely not.

Mukesh: I have several pictures which have been shot on the spot because I was carrying a camera. One evening I was going home early, I was passing railway harbour line called Reay Road station. A blast happened there, in the train bogey. People were thrown out...people were thrown out in the street, on the platform. No police, no fire brigade, local...other bogey people came to rescue...the tea stall owner on the platform rushed with water to give. Police, fire brigade, everybody came afterwards. I must be around, when the blast noise I heard, I must be on my two-wheeler around 200 metres away. I parked my scooter and went inside the platform. I saw a man dying in front of my eyes...you know...

Reema: So-

Mukesh: - I did not help him to survive, I shot my picture...

Reema Sengupta (the interviewer) witnessed an accident at Charni Road station and happened to have her DSLR with her. The victim's skull had broken open. She says, "I had a clear shot of the body from where I stood, but I just couldn't get myself to take the photograph. My conscience said it would be an inhumane, self-centered and disrespectful thing to do. The situation stayed on my mind for while after I had left the station. I thought I should've taken the picture. At least that way, I would have been able to bring the incident to light and help start a strong campaign to prevent train accidents. Also, no news channel or website made any mention of the incident, as if yet another train accident wasn't worth a mention. This incident got me thinking about the ethical dilemmas in photojournalism. I read up of Kevin Carter, the South African photojournalist who took the iconic imagine of a malnutritioned child in Sudan being waited upon by a vulture."

Carter committed suicide two months after receiving a Pulitzer Prize. (For more information on Kevin Carter, refer to :

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/ 0,9171,981431,00.html)

This brings us to the one of the main focuses of not only this interview, but the entire Photojournalism Series: the ethical dilemmas. To shoot or not to shoot. In a situation as the aforementioned, by taking the photograph and dispersing information to a large number of people, does one undervalue the life of the subject? What constitutes the greater good?

ethics

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: The way you told me, on the train incident.

Reema: Right, yes.

Reema: Well, what thoughts went on in your head then, because it wasn't like you had a brief or you were sent there on an assignment.

Mukesh: No no, it's not a brief. See, there is no brief coming in. In Daily newspaper or Indian Express or Mid-Day there is no brief coming in from anybody. You know, I run my team as an independent team catering to my editorial departments. Whether it is the seven newspapers of the Indian Express group or five of the Mid-Day group, I don't take a brief from my editor that er, what picture you want. See, basically we are hard news photographers. Brief comes when yeah, we are meeting Shah Rukh Khan - your light should be like this, your place should be okay, our page design is like that. In the features section, or in the magazine section when the art director has already planned something, there the brief comes in. But in the hard news, where is the question of brief?

Reema: Definitely, it's all about being spontaneous.

Mukesh: It is all about the spontaneity.

Mukesh: So, in 1980 there were the Bhiwandi riots, I have seen people being killed in front of me. I've seen in Ahmedabad...I was travelling on a scooter with the local reporter there. I saw a man riding in a curfew-bound area on a cycle. And then we went deep ahead, and then after five minutes we turned back and we came back to the same spot where this man's body lay and the cycle was lying there. I cursed myself that er, I, for a moment I had thought of it, ki I will shoot this man and the empty road. But I thought I may get something better, let's not stop. After I came back, I said I missed the picture.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: Here was a man alive, and here is the man dead.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: So it is all how things unfolds in front of your camera. There is no planning, there is nothing, even these days I don't shoot much but the camera is always with me in my car and whenever I find something I do shoot.

photo reference

Reema: I mean, you've taken some pretty radical pictures, even like the one right there. How do you think these visuals that you've captured have affected you as an individual? And also your photojournalistic practice.

Mukesh: You see, the lot of people say, "We don't want to show blood, we don't want to show agony, we don't want to show dead bodies." See, right now, in the last one week, how many natural calamities all around the world. What will you do? You have to shoot something. I saw some newspaper only carrying a body lying with a camera almost on the floor with the only shoes and the background. OK, that is quite a simplified, non-ghastly picture. But we have seen the picture, we have published the pictures. A man is buried in the house collapse...he's dead, his just only this much face is seen and the fireman is trying to cut the wood under which he is trapped. So those pictures have been published when you see that yes, it took time for fire brigade to reach and to try and if the story develops; you may not carry that picture very big, prominently. But you might carry inside.

By deciding whether a picture is 'too ghastly' to use, the editorial team is making a decision which amounts to some amount of censorship (in other words, withholding some information from the public). Would having all information in one place, without censorship or judgments, create a true and ideal Marketplace of Ideas?

In a sense, the internet has provided something in this vein, everything is out there for everyone to access. However, this, along with the barrage of visuals on television, has led to a great amount of desensitization among the public. In this situation, what is inherent in a photograph for it to have effect, or to go as far as becoming an iconic image?

editorial process

Mukesh: I have a picture of a bus driver who ran into another truck loaded with the iron rods. I could see iron rod piercing through from here to here, out. And he died in the driver's seat. This happened around 5:30-6:00 in the morning, I could land up at that place around 7:30 when the news came. In those days, all landline contacts...So we have used the pictures. There as a bomb blast in Congress office in Delhi...head got torn out and the policeman is carrying a head in his hand. The entire Delhi media used it, but at Indian Express in Bombay, we did feel no, we should not carry it, we did not carry it.

Mukesh: The international media jumped on the picture and they used it, I am sorry to tell you, that anything such things happen in India the western press highlights those pictures. But when something happens at say, like America, terror attack...September, we...no pictures...no pictures. Ground Zero...shoot Ground Zero, that's all. Only what live coverage went to the local people who were shot with the videos, that went on channel.

Reema: Right, yes.

Mukesh: I will tell you, I travel to Kuala Lumpur, I travel to Singapore...I spent 15 days in Japan jumping from one city to another for ten days. All ten cities I saw the same kind of people, same kind of living, same kind of houses. Japan. Today if you ask me where is this picture in Japan I will not be able to tell you except the pictures of Hiroshima and Tokyo, which are well known places or may be er, very popular places. Identical, everything is same. In India, by and large 5,000 photographers visit India every year to shoot India. Why? Because you start from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. You have a variety of pictures, variety of life, variety of people...which doesn't exist (in Japan)...

Reema: Well. Let's talk about censorship. How do you feel about your photographs being censored?

Mukesh: Who will censor?

Reema: Well, when you were a photojournalist did you have a Photo Editor...who was-?

Mukesh: I was the Photo Editor with the Indian Express. I was the Chief Photographer with Daily. Yes, we had arguments, we ad discussions, we had difference of opinion with the News Editor who finally puts the picture on the page. We had quite a few issues when something happened or something...but by and large when we are giving every week one scoop picture, every week exclusive events, and if we feel that yes we should not carry this...

censorship

editorial process

People tend to believe what they see in a photograph, it is sometimes considered the absolute truth. However, there are so many filters in the way. It begins at point of the photographer's intent, to the actual decisive moment where the photo is made, after which it (along with others snapped) is considered by an editorial team. Which picture is chosen, its juxtaposition with text and/or other images, its placement, etc. all play a huge role in creating public opinion.

The following excerpt explains further:

"Like any system of representation, photography can deny circumstance and expurgate unpleasant reality. Its inherent accuracy and detail of rendering invite censorship, masking and alteration for the sake of decency. (page 53)

What the media show in photojournalism must be newsworthy but not too detailed. Consequently, it will differ from police or forensic photographs presented as evidence in court, which lawyers shield from the public gaze. It is tempting, but erroneous to describe this editing and sifting as a conspiracy of censorship which denies the public what they have a right to or what they want, to see. Censorship does not stand aloof, but is part of the process of establishing consensus among

publishers; it too changes over time, and in different publishing and broadcasting arenas. There is nothing about the censorship of the media or about its own self censorship which is fundamentally different from other ways of communicating in public in everyday life. Regulation is the norm, whether it is effective at the micro-level of the individual or, failing that, at the macro-level of civil society. Not everything that can be seen or said is in fact shown or spoken, and authorities of everystripe exact penalties if they think one sector of their industry has published unacceptable sights and sounds. (page 83)"

Taylor, John, 1998, Body horror: photojournalism, catastrophe, and war, New York University Press

Reema: So it's more about censoring yourself.

Mukesh: Censoring yourself.

Reema: Applying your own personal sense of...

Mukesh: You need self-discipline. You need self-discipline.

Reema: Do you feel in today's... media, I'd say, censorship is being used sort of as a tool for sensationalism?

Mukesh: You see I will tell you, I will not name the celebrity. One freelance photographer brought the picture of a lady actress sitting in a public function with the skirt, small skirt, and the legs like this. Her lower part was exposed to the camera because photographer was sitting on the floor to avoid the dais being shown.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: We showed that picture to the editor...and I said, "We should not use it." Then we did not use it. But after I left Mid-Day, that celebrity became very NEWSY...related to her dressings and her costumes and her style of ear-ring and in the specific story to that angle, they used that picture. So...here the things go.

Mukesh: So sometime what one feels that you should need a self-discipline, you should not even show such pictures to the newsroom so that they can recollect. I had marketed a CD about ten years back of the Bombay pictures, the street pictures, and that went on as a big campaign in the Times of India where they did four-page supplement and people still remember those pictures, and yesterday again I got a call from Bangalore - that "we are looking for those pictures." So people do remember your pictures and the...

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: ...When you specifically shoot the picture, select the picture, put them in the proper perspective in the newspapers or the magazines.

Reema: Right, then they do appreciate and remember your work.

Mukesh: Yes, they do appreciate.

Reema: I think we'll have to take two minutes.

Mukesh: Yes.

Mukesh: I'll show you again when I enlarge it, ok?

Reema: Yeah, sure.

Mukesh: I'll just tell you what I have right now.

Reema: Oh god, ok.

Mukesh: See, this is Mrs. Gandhi in raincoat - have you ever seen her?

Reema: Haha hmm, no.

Reema: And, obviously it's their job to take the photos and not to help people out there.

Mukesh: I told you about the networking - how I had to push my person on the spot as early as possible.

Reema: Right, but lemme...especially in cases when here has been an accident or something of that sort -

Mukesh: You see in these days, when the railway blasts were happening in the different...

Reema: Stations.

Mukesh: Stations. I alerted all the men to be in the vicinity of that train, the western railway line, one of them WAS in that train - but not in the bogey but in the other bogey, and he started shooting the pictures. Like I saw it on the Reay Road, he was in that train itself but in other bogey.

Reema: Oh, okay. So what, I mean, once you've gotten the picture, do people - do photojournalists sort of try and help out

because they're...not really?

Mukesh: I have not seen. You know, by the time help arrives. It is not that we have avoided the help...by the time, help arrives, help is there.

Mukesh: So this was the ghastly picture I wanted to show you.

Reema: Oh god, yeah.

Mukesh: Now this is a big fire, and this is sun. This is not a star. But see how thick black smoke is there, that afternoon sun is so hidden. And using a slower shutterspeed and the smaller aperture, gave me the star effect of the sun.

Reema: Also, a lot of the times, I mean, how do you aesthetically decide to compose a picture? Or is it just the technical and creative decisions that you make?

Mukesh: You see, these days you are surrounded by so many photojournalists. Now this Amitabh Bachchan was a scoop. He walked down from his home in Prateeksha at Juhu upto Siddhivinayak Temple with wife and son, walked. We got the tip-off around 11:30`at night. I parked my two photographers at Prateeksha. Moment he started walking, I was alerted. I put another person between Bandra and Mahim, and myself and another person waited for him to arrive in Siddhivinayak, which was 4:30 in the morning because temples opens around quarter-to-five. So we had a whole series of pictures - right from coming out from home - no newspaper has.

1. Henri Cartier-Bresson's concept of The Decisive Moment can apply in an aesthetic sense too. If you are waiting for a certain person to walk into the frame at a particular moment (because this will visually enhance the photograph), it amounts to the same thing. Refer to the Interview with Chirodeep Chaudhary, part of the same series, where this is discussed in further detail.

2. Aruna Shanbaug's photograph brings is to an important issue: consent and privacy. Aruna Shaunbag is clearly not in a position to give her consent, however permission was given by the authorities at K.E.M. Hospital. How important is the subject's consent? What does one do when the subject is NOT in a position to say yes or no?

Nisha: Could you say that again, please?

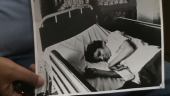

Mukesh: Yeah. Aruna Shanbag picture, I shot it in 1980 when I was freelancing and I was just trying to settle down in the media. '79 I started freelancing. '80 a newspaper called Mid-Day was launched, and I was freelancing for them and my duty was to get different pictures than their staffers. So I saw the story about the Aruna Shanbag appearing everyday, but no one was getting a picture. So I went and tried my best in the K.E.M. Hospital and with the great persuasion and...persuasion...I managed to got [sic] permission to shoot few frames.

Reema: Right.

Who was Aruna Shanbaug? An excerpt from a Times of India article by Pinki Virani:

Aruna was on duty one November night in 1973 at the King Edward Memorial Hospital when a wardboy-cum-sweeper of the hospital, Sohanlal Bharta Valmiki, accosted her, wrapped a dogchain round her neck and while beating her brutally, raped her.

He took her earrings and watch and left her there, bleeding, till the next morning. He also took with him, her power of speech, her capacity to move and her eyesight.

In throttling her with the chain, he had shut off blood supply to the parts of her brain that are responsible for these functions.

The case made headlines, there was national outrage. Letters of protest poured in from the medical fraternity of Mumbai. Sohanlal was arrested in Pune.

His case came for hearing the following year by which time, he had already spent a year in jail. He was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for stealing, and another seven years for having tried to harm her fatally. Both sentences were to run concurrently. As he had already spent a year behind bars, six years later, he was a free man. He took up a job as a wardboy in a Delhi hospital.

He was never tried for rape because no one had lodged a complaint and during the medical examination, Aruna's hymen was found intact. The court decided there was no rape.

Mukesh: And that was used in the Mid-Day in those days as a scoop. I can say that was my big scoop.

Reema: Can we take a look at it?

Mukesh: Yeah, you can, sure. This is the print as it is lying still with me, and recently again the story broke - The Times of India used it.

Reema: Right, the picture?

Mukesh: Yes, lot of channels also picked up this picture from the newspapers. From time to time, only two newspapers accept this picture - myself and one from the another newspaper.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: So this is the style we always keep chasing the story - whether we get picture today, tomorrow, day after...

Reema: So well, she's still lying in the coma in the same place, right?

Mukesh: Yes, yes.

Reema: So did you like, try to go back and get some pictures later, how did that work out?

Mukesh: We have got pictures, but it is not easy to get an access because she is under constant care of the staff of K.E.M. Hospital, and I would say pretty well care taken. The family has visited her but the hospital hasn't, so I will say I would not love to discuss them every now and then. But talking about the scoops we keep chasing, I will tell you the another story of the Pravin Mahajan, who killed the Pramod Mahajan in his house.

Reema: Yeah, right right.

Mukesh: There was a function in the jail by Sri Sri Ravishankar team.

Reema: Right, Art of Living.

Mukesh: Art of Living. So we managed to get into that Art of Living event inside the jail -

Reema: Okay.

Mukesh: - where Pravin Mahajan was also part of being taught yoga and the meditation and so we got Pravin Mahajan inside also. Similarly, the day story broke out we were trying to get the family of Pravin Mahajan - wife, son, daughter - but we were all the time ditched, we could not get her. But I never gave up. I got his family - wife, son, daughter - outside Arthur Road Jail. We had a tip-off that one particular day every week they come.

Pravin Mahajan's death reported in The Hindu:

Mumbai: Pravin Mahajan, 50, convicted of the murder of his brother and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader Pramod Mahajan, died on Wednesday at a hospital in Thane where he was undergoing treatment for brain haemorrhage.

Mr. Mahajan had been in a coma for about two-and-a-half months, since he was hospitalised on December 11 in an unconscious state and diagnosed with a clot in the brain.

He is survived by his wife, Sarangi Mahajan, and children, Vrushali and Kapil. He had been out of the Nashik Central Jail since November 27, 2009 on a 14-day furlough. However on the last day of the parole period, he suddenly took ill.

Dr. Ravindra Ghawat, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in-charge, told a press conference in Thane that Pravin Mahajan was "declared dead" at 5.40 p.m. The cause of death was "extensive pontine haemorrhage [brain haemorrhage] with sepsis and multi-organ failure."

Murky chapter ends

Pravin Mahajan's death puts an end to a murky political chapter in the State BJP.

Pramod Mahajan, who wielded considerable influence in his party, was shot at thrice by Pravin Mahajan on April 22, 2006 at the former's Worli residence in Mumbai, following a dispute. Pramod Mahajan succumbed to his bullet injuries on May 3, 2006.

It was Pramod Mahajan who supported Pravin Mahajan in his early years and even provided him education. The latter was a small time contractor, while the former was making it big in the BJP.

Mukesh Parpiani's office, Piramal Art Gallery.

Reema: Tip-off from the police?

Mukesh: Yes. Or from the jail when they come. Twice, thrice we missed it by five minutes or ten minutes, but after 100 days we did got her outside the jail. So imagine that we have a list with us - what is done and what is still left out on our menu! The moment we got the tip-off we landed up in the jail in ten minutes and we got once again, it was a Mid-Day scoop, talking to her outside the jail.

Reema: One question I wanted to ask was - how important is the subject's consent? I mean, if there's a situation where the subject objects to being photographed, or a situation where the subject is not in a state to either consent or to object, then we know for a fact that photojournalists -

(Camera falls.)

Nisha: Sorry.

(Camera back in place.)

Nisha: We'll chop that bit off.

Reema: Yeah, let's just. I'll start again.

photo reference

Reema: Well, talking about consent, how important is the subject's consent in photojournalism? I mean, if there's a situation where the subject objects to being photographed, or a situation where the subject is not in a state to either consent or object to being photographed, what does the photojournalist do? What SHOULD the photojournalist do?

Mukesh: You see, as far street is concerned, road is concerned, public place is concerned, no one can stop you from taking that picture.

Reema: Legally, like, by law?

Mukesh: Legally, nobody can stops you. But, again legally, you cannot use that picture commercially without his or her consent. For the media, newspaper, print media, channel-

Reema: Does that include photography exhibitions?

Mukesh: Yes. Obviously you cannot sell that picture but you can shoot in the public places, you are legally safe. Like you were shooting in the streets of Colaba, nobody had the right to stop you. But the hawkers, people on the street say, "This picture is published, the BMC will come and arrest us." because you know that hawkers feel that they are given a 4x4 ft stall but they have made 10x10 ft stall, the moment it is seen in the newspaper they come into the trouble. So they try to chase you because of that. You know but er...

Mukesh: We have gone inside the house of the celebrities and shot. I went in some - the house, of Mrs. Telgi's house. Telgi was in the jail, nobody had a picture of Mrs. Telgi. I have a picture of Mrs. Telgi staying beside the...behind the Taj Mahal Hotel.

Reema: But that was with consent?

Mukesh: No.

Reema: No, it wasn't...so can't -

Who was Abdul Karim Telgi? An excerpt from an article at

boloji.com by Rajinder Puri (

http://www.boloji.com/myword/mw043.htm) tells us:

Mr. Telgi is the public face of the hidden mafia behind the nationwide fake stamp papers scam. It is India's biggest ever scam. CNN-IBN said Mr. Telgi made Rs 30,000 crore. He did not. He generated Rs 30,000 crore. This scam makes a mockery of national security. It exposes a dangerously compromised political class and a soft state incapable of containing terrorism...

...Meanwhile, terrorism got a tremendous boost. Fake currency was manufactured by terrorists to fund their operations.

...Investigators were amazed at the sophistication of Mr. Telgiï's operation. He had employed MBA graduates to prepare his project report. Mr. Telgi's clientele included 52 builders, 48 banks, and 61 top companies. Did government audit the accounts of these companies to find out whether Mr. Telgi sold them stamp paper at a discount? Leading politicians whose names cropped up during the Telgi probe included MLAs Mr. Anil Gote, Mr. Roshan Baig and Mr. Krishna Yadav. They were all arrested. Other names that figured in police leaks to media included former Karnataka CM and current Maharashtra Governor, Mr. SM Krishna, former Maharashtra CM, Mr. Narayan Rane, former deputy CM, Mr. Chhagan Bhujbal, and the current CM, Mr. Vilasrao Deshmukh. From the BJP, apart from Mr. Jethmalani and Mr. Yashwant Sinha, the name of Mr. Gopinath Munde figured. Apparently Mr. Telgiï's polygraph test revealed the biggest political names.

Mukesh: We put a small Coolpix camera like this, with a jacket. She came and sat with us. One of my colleague who knows her language started talking to her about the Telgi and all that - and how did er, much money did they make, are you aware of it - that woman is a simple woman, she doesn't know anything. She has a daughter studying in the Sophia College in those days. Basically, we went to shoot her. Mother and daughter. Because story was that the daughter is studying in that college under a fictitious name.

Reema: Ooh...

Mukesh: With the permission of the college, that nobody raises their finger at her that she is Telgi's daughter. On paper yes, but as eh, other students, nobody knew -

Reema: -that she was Telgi's daughter. So did you manage to get her picture, the daughter's?

Mukesh: No, we missed that.

Reema: But if you would've gotten the picture, would you have published it?

Mukesh: But after...we saw her! We saw her there, she came and sat there for a brief minute but we were not ready to shoot at the particular point.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: Then she got up and went away, because she had somebody at the entrance.

Reema: Okay.

Mukesh: Then she took that guest to the other room, we missed that, we got Mrs. Telgi. The whole idea was to -

Reema: - get both of them.

Mukesh: But then we could have tried second time also. But then the our conscience felt that -

Reema: - that if she's doing so much to conceal her identity -

Mukesh: - let's not disturb her privacy. We did use Mrs. Telgi's picture, but then we gave up, we said let's forget it, let her continue her studies peacefully.

Reema: Right, of course.

Mukesh: Let her be, you know. Your intuition tells you what to do.

Reema: Of course.

Reema: You mentioned when you moved to Mid-Day everything was completely digitalised. How did the digital camera sort of change or influence photojournalistic practice?

Mukesh: I will give you a very big story about this.

Reema: Sure.

Mukesh: Digital camera Nikon B1, when we bought the first camera, it costed [sic] us 4 and a half lakh rupees. My boss at Mid-Day told me, "Are you mad?! In 4 and a half lakh rupees, you can buy a flat in Mira Road. I'm not buying it...I'm not buying it."

"Introduction of digital photography in photojournalism brought forth an entire new debate about the ethics surrounding photojournalism."

John Long, Ethics Co-Chair and, Past President NPPA, has said in his Ethics in the Age of Digital Photography, 1999:

"The advent of computers and digital photography has not created the need for a whole new set of ethical standards. We are not dealing with something brand new. We merely have a new way of processing images and the same principles that have guided us in traditional photojournalism should be the principles that guide us in the use of the computers. This fact makes dealing with computer related ethics far less daunting than if we had to begin from square one."

He has also stated:

"One of the major problems we face as photojournalists is the fact that the public is losing faith

in us. Our readers and viewers no longer believe everything they see. All images are called into

question because the computer has proved that images are malleable, changeable, fluid. In

movies, advertisements, TV shows, magazines, we are constantly exposed to images created or

changed by computers. As William J. Mitchell points out in his book, The Reconfigured Eye, Visual

Truth in the Post-Photographic Era, we are experiencing a paradigm shift in how we define the

nature of a photograph. The Photograph is no longer a fixed image; it has become a watery mix of

moveable pixels and this is changing how we perceive what a photograph is. The bottom line is that

documentary photojournalism is the last vestige of the real photography.

Journalists have only one thing to offer the public and that is CREDIBILITY. This is the first vocabulary

word I want you to remember, and the most important. Without credibility we have nothing. We

might as well go sell widgets door to door since without the trust of the public we cannot exist as a

profession."

Mukesh: We pressurized him, we made him buy. We bought one piece for all of us -

Reema: The whole team.

Mukesh: - that use it at the time of deadline pressure. So that immediately you shoot and come and do it. After one month, my editor was going to Afghanistan for a war coverage. He said, "I am taking away your camera." I can't say no to the editor! He took away the camera. He was crossing a river. He did shoot the pictures, he did email us the pictures with that camera.

Mukesh: One fine day he was crossing that river on a horseride. Everything was warzone, Afghanistan. Suddenly, horse went berserk, fell down in the river bank - camera bag, laptop, everything in the water. Came back, no camera. We had no face to show to our chairman, Mr. Ansari, that we lost the camera.

Reema: Oh, god.

Mukesh: Camera was sent to Singapore for repairs. Singapore sent it to Japan, we got it back after one year. No insurance, because he left last minute for Afghanistan. So we had no insurance, we had to pay again.

Reema: Oh, god.

Mukesh: So this is the style, life. And then the prices started crashing and we went on buying the -

Reema: - more cameras.

Mukesh: More cameras. We started with Coolpix first, then we went to SLRs.

Reema: Right. Well, I mean, when you use film, obviously film is expensive and it'll be company-sponsored, obviously. So I'm guessing the photojournalists had to be very careful about each shot that they take.

Mukesh: See, it is like that and the big newspapers never made any fuss about how much film you used. But smaller newspapers had a monthly budget for the photographers: like, you manage in this. Some newspapers of regional newspaper used to question photographers that, "You've got 36 frames and we have used only one picture, and you're wasting so much film?"

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: Obviously when you are covering a newsroom you can't think what could happen again. Yeah you're shooting a portrait, okay you shoot 20 pictures, that's fine, enough from that. But you were covering a whole day bandh in city, you need to shoot at least 100 pictures in a day to choose five pictures for the evening. You can't go back and choose. But those administrative account people in those days were disaster, you know.

Reema: So well, digital cameras have made things much easier.

Mukesh: Arrey but digital created problems, haha.

Reema: For you'll, yes, haha.

Reema: Right. Um, how would you define the role of photojournalism; what purpose is it supposed to serve?

Mukesh: To present to the your reader what your cameras sees it. Not create it. Let person read your picture as you shoot it, don't manipulate it.

Reema: Right.

Reema: When you take a picture, what...to what extent do you think does the photograph, as a photojournalist, actually have an impact in society?

Mukesh: It's lot of impact, as I told you, people still remember my pictures. They called me, I mentioned to you, they called me up from Bangalore yesterday that, "We are looking for your so-and-so specific picture."

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: Which is not that popular but they had in mind, they have saved the clippings.

Mukesh: I will tell you in 1984 I went to cover the funeral of Mrs. Gandhi in Delhi. The Daily newspaper covered the two-page splash. And last week somebody found that paper in raddi newspaper stall. That person was, must be, looking for something else in the newspaper, and he remembers my name - he remembers me as the guy working for Mid-Day; he called up Mid-Day person, that I want to speak to Mukesh Parpiani, I have found a page for him which is 1984 Mrs. Gandhi's funeral. Even I have not preserved that page.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: Because in those days who is going to keep newspaper bundles? Newspaper library keeps it, so we don't keep it personally -

Reema: So all your photos, used and unused, all go in -

Mukesh: I've got with me negative form, yes. Negative and print form, yes. But the published form, no.

Reema: Right, of course. Well, of all the photos that you take, the used ones of course definitely go into the newspaper archives. What happens to the unused ones?

Mukesh: Unused ones remain in the negative form in the -

Reema: With the photographer or with both of them?

Mukesh: Both of them. Somebody keeps with him, somebody gives it with the newspaper library. Most of them keep with them only.

Reema: Right.

Mukesh: So this man took a trouble to bring that page to the Mid-Day office and has left it there, and he found out my number from there and called me up that, "I have left your page." So this is the world, is small.

Reema: Right, definitely. Alright, it was really nice talking to you, I think we had a very insightful discussion.

Mukesh: Yes, yes.

Reema: Thank you so much.

Mukesh: Alright.

Nisha: Thank you.

Pad.ma requires JavaScript.